Ultrasound-driven “bubble muscles” turn sound into programmable motion—no wires or batteries. See what it means for soft robots, implants, and AI control.

Ultrasound Bubble Muscles for Soft Robots and Implants

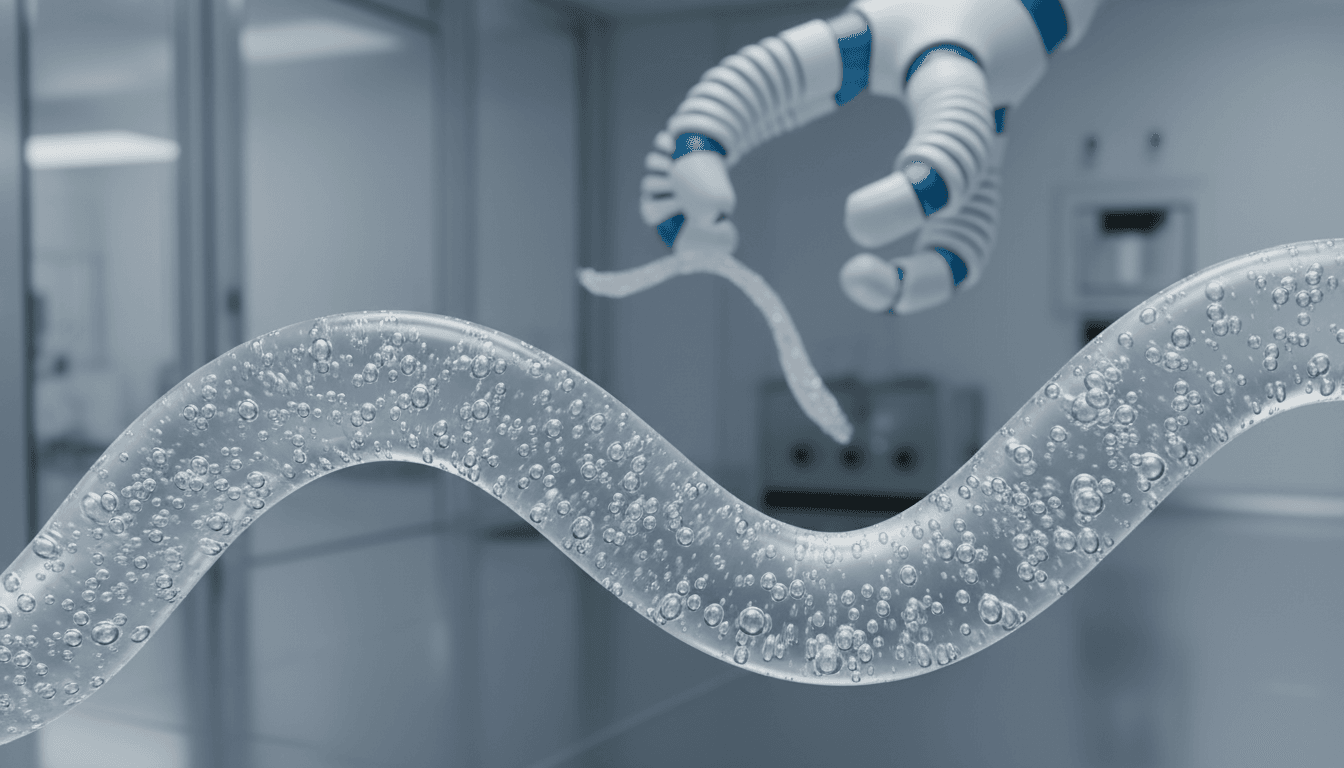

A bandage-sized patch gripping a beating heart sounds like science fiction. Yet in a recent Nature report, researchers showed a soft gel packed with microbubbles that can contract and bend under ultrasound, sticking to pig heart tissue for over an hour while flexing on command. No wires. No onboard batteries. No pneumatic tubing snaking back to a pump.

Most companies building robots for healthcare and inspection keep running into the same wall: actuation. Sensors and AI keep getting better, but the “muscles” that move machines are often rigid, bulky, noisy, or hard to sterilize. Bubble-powered artificial muscles are interesting because they attack the bottleneck directly—and they’re naturally compatible with AI-driven robot control: programmable motion, external energy delivery, and a feedback path through imaging.

This post is part of our “Artificial Intelligence & Robotics: Transforming Industries Worldwide” series, and it’s a strong example of where robotics is headed next: human-centric automation that’s soft, safe, and controllable inside places traditional robots can’t go.

Bubble muscles: the plain-English explanation

Bubble muscles are soft actuators that turn ultrasound vibrations into motion by making embedded microbubbles resonate. That resonance creates local deformations in the gel—bending, twisting, contracting—depending on how the bubbles are arranged and what frequency you send in.

The core trick is simple: the researchers embedded thousands of microscopic air bubbles into a biocompatible gel and patterned them in lattice-like arrays. When ultrasound hits the material, the bubbles respond like tiny springs. Importantly, different bubble sizes respond to different frequencies, which means you can “address” different regions of the gel by changing the ultrasound frequency.

That’s the step change versus many soft robotics approaches:

- No tethered pumps (common in pneumatic soft robots)

- No internal batteries (a major constraint for implants)

- No heating elements (which can be slow and medically tricky)

- Fast response (acoustic resonance is quick)

“By activating different sets of frequencies, you can actually get programmable muscle.” — Daniel Ahmed (ETH Zürich), as reported in the RSS summary

Why robotics keeps struggling with artificial muscle design

Artificial muscles fail in the real world for three reasons: packaging, control, and safety. You can build a lab demo that flexes nicely, but deploying it in a product—especially in healthcare—usually exposes ugly constraints.

Packaging: the hidden enemy of soft robotics

Soft actuators often need “hard” support systems. Pneumatics need pumps, valves, tubing, and seals. Hydraulics add fluid management and leak risk. Electrically driven polymer actuators need drivers, insulation, and thermal management. All that hardware undercuts the promise of softness.

Bubble muscles shift packaging work outside the device: the ultrasound source can be external, and the implant/robot stays mechanically simple.

Control: you can’t automate what you can’t reliably steer

AI control is only as good as the actuator model behind it. Many soft actuators have hysteresis, drift, or slow response, which makes closed-loop control messy.

In contrast, frequency-based addressing of bubble arrays looks like a control engineer’s dream: the “command space” becomes frequencies and pulse patterns, not complicated pressure profiles.

Safety: healthcare robots don’t get to be “mostly safe”

Motors and rigid transmissions can pinch or tear tissue. Heat-driven actuators can create hot spots. Chemical actuators can introduce biocompatibility concerns.

Ultrasound is already widely used in medicine, and the material itself is designed to be biocompatible—so the safety conversation starts from a more practical place.

What the prototypes tell us (and what they don’t)

The demos matter because they show multiple operating modes: gripping, swimming, patch adhesion, and deployment inside tissue. A single “muscle” concept that can do all of that usually signals a platform technology.

A gentle gripper that can handle living tissue

One prototype gripper closed around live zebrafish larvae without harming them. That’s not just a cute demo. It’s a proxy for an industrial requirement: high compliance plus reliable grasping.

If you’ve ever worked with delicate items—cell cultures, thin membranes, soft fruit, flexible electronics—you know the pain: rigid grippers either crush the object or fail to grip. Soft grippers often grip gently but inconsistently.

Bubble muscles suggest a middle path: gentle contact with fast snap-through motion when commanded.

A stingray robot that moves where wires don’t

Another prototype was a stingray-shaped soft robot whose fins had three bubble sizes, enabling different responses under ultrasound. It swam smoothly through water—and notably, it also demonstrated motion inside pig stomach tissue (non-living tissue in the reported work).

From an industry perspective, this is the real headline: deep access with external power delivery. That’s relevant for medical navigation and for non-medical inspection tasks in tight, tortuous spaces.

Tissue patches that stick and flex

The heart patch demo—staying attached for more than an hour while flexing—hints at a new class of devices: active patches.

Instead of a passive bandage or drug depot, imagine a patch that:

- Conforms to moving tissue

- Applies micro-massage or mechanical stimulation

- Holds position while delivering drugs

- Responds to commands without a battery

That’s a credible direction for smart biomedical implants, especially for short-to-medium duration therapies.

Why this is “AI-compatible” robotics (and not just a materials story)

AI needs actuators that are controllable, observable, and scalable. Bubble muscles check all three boxes.

Programmability: frequency becomes the control language

With bubble arrays, motion can be selected by:

- Ultrasound frequency (which bubble size responds)

- Pulse timing and duty cycle (how strongly and how long it actuates)

- Spatial arrangement of bubbles (what deformation mode emerges)

That lends itself to AI control methods like reinforcement learning or model predictive control, because the input space is compact and measurable.

Observability: ultrasound can also “see” the actuator

A practical robotics system needs state estimation. The RSS summary highlights a strong advantage: microbubbles can be tracked by standard ultrasound imaging.

Even better, the actuation frequencies (reported as 1–100 kHz) are far below clinical ultrasound imaging frequencies (~1–20 MHz), so control and imaging can coexist without stepping on each other.

That opens the door to a closed-loop stack that looks like this:

- Imaging estimates actuator shape/position

- Controller selects frequency + pulse pattern

- Actuator deforms

- Imaging confirms result

That feedback loop is where AI becomes useful, especially in messy biological environments.

Scalability: external energy delivery simplifies deployment

When power is external, onboard complexity drops. That’s attractive for:

- Small devices (capsules, patches, micro-robots)

- Sterile environments (less electronics to seal)

- Single-use tools (lower bill of materials)

This is the same reason many teams are excited about magnetic actuation and optical actuation. Ultrasound joins that club—with a nice bonus: it already has a clinical footprint.

Real-world constraints you should take seriously

The biggest risk is translation: dead-tissue demos are not living-body performance. The RSS summary calls this out clearly, and I agree with the skepticism.

Constraint 1: ultrasound propagation in living anatomy

Bones, gas pockets, and irregular tissue boundaries can scatter or attenuate ultrasound. Inside a living body you also have perfusion, fluid flow, and motion.

What needs to be proven in vivo:

- How precisely can the system target actuation through heterogeneous tissue?

- What is the effective range and angle tolerance?

- Does actuation remain stable under blood flow, peristalsis, or respiration?

Constraint 2: bubble stability over time

The summary notes a key limitation: prolonged actuation causes bubbles to expand and destabilize after around half an hour.

That’s not a deal-breaker, but it defines the early product envelope. Near-term applications should assume short actuation windows or intermittent duty cycles, and designs may need bubble “refresh” strategies or materials that limit coarsening.

Constraint 3: safety, heating, and regulatory evidence

Even with ultrasound’s clinical history, regulators will demand:

- Local temperature rise under prolonged actuation

- Tissue damage thresholds for the specific frequencies and intensities used

- Failure modes (detachment, migration, fragmentation, biodegradation byproducts)

If you’re building a roadmap, budget time for boring work: biocompatibility, sterilization validation, and reproducibility of bubble size distributions.

Where bubble muscles can create value first (healthcare and beyond)

The first wins will be in niche, high-value workflows where softness, wireless control, and small form factor beat raw force output. Here are realistic paths.

Near-term healthcare use cases

- Active drug-delivery patches for internal tissues (e.g., bladder, GI tract), where the device deploys from a capsule and then anchors.

- Soft endoscopic tools that articulate without internal motors near delicate tissue.

- Temporary post-op assist devices that provide gentle mechanical stimulation to reduce adhesions or support healing.

A practical stance: the sweet spot is short-duration actuation (minutes) and precise positioning (imaging-assisted).

Industrial and lab automation use cases

Healthcare won’t be the only beneficiary.

- Gentle handling in food processing (berries, pastries) where bruising is costly.

- Flexible electronics assembly where thin substrates tear easily.

- Bio lab automation handling organoids or fragile samples with compliance.

In these settings, ultrasound delivery is simpler than in vivo, and the reliability bar—while still high—is more manageable.

How to evaluate this tech if you’re an operator or product leader

Treat bubble muscles as an actuator platform and score them against your environment, not against a motor on a bench. Here’s a fast checklist I’ve found useful when vetting soft robotics concepts.

- Power delivery: Can you place an ultrasound source close enough, consistently enough, for your workflow?

- Control resolution: Do you need millimeter-accurate bending, or is coarse motion fine?

- Duty cycle: Does your task fit inside a 10–30 minute actuation window (or intermittent pulses)?

- Sensing and feedback: Will you use ultrasound imaging, external vision, or embedded strain sensing?

- Sterility and disposability: Is this single-use, reusable, implantable, or external?

- Failure modes: What happens if actuation weakens—does the system fail safe?

If you can answer these early, you’ll know whether to pursue a pilot or wait for the next iteration.

What this signals for the broader AI + robotics shift

Bubble muscles are a reminder that AI progress alone doesn’t deliver capable robots. The next wave of automation will come from stacks where materials, actuation, sensing, and learning are designed together.

This is why the “Artificial Intelligence & Robotics: Transforming Industries Worldwide” theme matters: real impact shows up when robots become more human-compatible—soft where they touch us, smart enough to adapt, and practical enough to deploy.

If ultrasound-driven artificial muscles can prove themselves in living systems, the most interesting outcome won’t be a single robot. It’ll be a design pattern: wireless, imaging-visible, AI-controlled soft machines that work inside bodies, inside pipes, and inside tight manufacturing setups.

So here’s the question I’m watching into 2026: when actuators become programmable materials, how quickly will robotics teams stop “building robots” and start “printing behaviors” into the hardware?