Rugged robot grippers, touch sensing, and LLM planning show what actually scales in industry. Learn what to evaluate before deploying humanoids.

Robot Hands That Work: Rugged Grippers & Real AI Use

A humanoid robot with a delicate, five-fingered hand looks impressive right up until it faceplants. That’s not a hypothetical—falls are a normal part of deploying robots in the real world, especially in warehouses, factories, hospitals, and construction sites where floors are slick, spaces are tight, and “unexpected contact” is basically the job description.

That’s why one of the most practical signals in this week’s robotics roundup isn’t a flashier humanoid torso or a smoother walk cycle. It’s the shift in thinking behind robot grippers: design for impact, design for the task, and don’t assume a robot needs to mimic human anatomy to be useful.

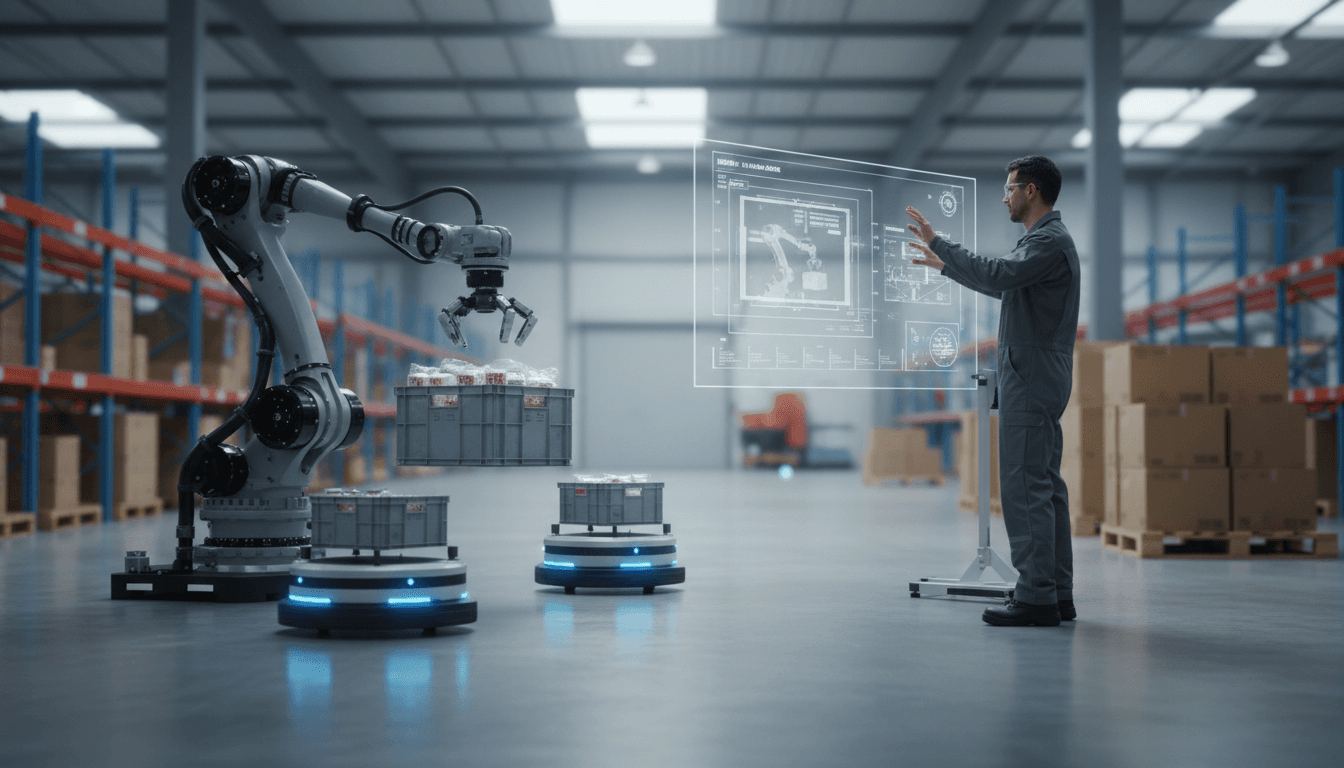

This post is part of our “Artificial Intelligence & Robotics: Transforming Industries Worldwide” series, and the theme here is simple: the robots that change industries aren’t the ones that look the most human—they’re the ones that work reliably, integrate cleanly, and deliver measurable ROI.

Rugged robot grippers beat pretty hands (most of the time)

Answer first: If you want industrial automation to scale, prioritize durability and task fit over human-like hands. Five fingers are rarely required, and they often introduce fragility, control complexity, and maintenance costs.

Boston Dynamics’ discussion around grippers hits two points that I wish more humanoid teams would say out loud.

Design for the fall, not the demo

Most robotics demos are filmed in controlled environments. Real deployments aren’t. A robot that’s expected to handle boxes, totes, carts, tools, or medical supplies will eventually:

- collide with shelving

- clip a doorway

- get bumped by a pallet jack

- slip on debris

- fall (yes, even if it’s “rare”)

A gripper designed with inevitable impact in mind changes everything: material choices, protective geometry, compliance, and how you route cables and actuators. In many operations, mean time to repair matters as much as mean time between failures.

Here’s a stance I’ll defend: a “good enough” gripper that survives 1,000 shifts wins over a dexterous hand that survives 100. The economics make the decision for you.

Stop forcing robots into a human range of motion

Human hands are miracles of evolution… for humans. Robots don’t share our constraints. A robot doesn’t need to play piano to pick cases, load a CNC, or bag pharmacy orders.

In practice, most commercial grasping falls into a few families:

- Parallel jaw grasps (boxes, trays, cartons)

- Power grasps (handles, cylinders, tools)

- Suction-assisted grasps (flat-packed items, plastic wrap, irregular packaging)

- Underactuated or compliant grasps (variation-tolerant handling)

If your use case is 80% “pick this thing up safely and put it there,” a rugged end effector plus solid perception often beats anthropomorphic complexity.

Touch is becoming software: force sensing + deep learning

Answer first: The next leap in human-robot interaction is touch perception without fragile add-on skins, using force sensing and machine learning to infer contact location, intent, and even symbolic input.

One of the most industry-relevant items in the roundup is the idea of robots that can feel where you touched them, recognize symbols, and support “virtual buttons.” This matters because it lowers the barrier to safe, flexible collaboration.

Why “natural touch” changes deployment economics

In many facilities, the hard part isn’t getting a robot to move—it’s getting people to work around it confidently. If you can make interaction intuitive, you reduce training time and operational friction.

Practical examples that already map to real workflows:

- Touch-to-pause: Tap a safe region on the arm to pause motion when a human needs access.

- Touch-to-teach: Guide a robot along a path, with the controller learning constraints and preferred trajectories.

- Virtual controls: Draw a quick symbol on a robot surface (or tap patterns) to switch modes—gloves on, no tablet required.

The deeper point: sensing isn’t just hardware anymore; it’s inference. A force/torque signal combined with a learned model can estimate contact location and classify intent. That’s a big deal for collaborative robots, mobile manipulators, and service robots that need to be “operable” by non-roboticists.

Safety isn’t a checkbox—it’s a user experience

Safety standards matter, but day-to-day safety is also behavioral. When touch interaction is predictable, workers trust the system. When it’s confusing, they bypass procedures.

If you’re evaluating AI-powered robotics for an industrial setting, ask vendors:

- What happens on unexpected contact?

- How does the robot communicate state (moving, paused, faulted)?

- Can a line worker safely intervene without a tablet or supervisor?

Those answers are often more revealing than a glossy demo.

LLMs are showing up in robotics—starting with choreography

Answer first: Large language models (LLMs) are becoming useful in robotics when they convert high-level intent into structured plans—like drone swarm choreography—while still enforcing safety and constraints.

A drone swarm performance might sound like entertainment-only, but it’s a preview of a serious pattern: using a language interface to specify what you want, then having software produce how to do it.

Swarms are constraint problems, not just “cool flights”

Coordinating dozens (or hundreds) of drones requires managing:

- collision avoidance

- timing synchronization

- geofencing and no-fly volumes

- battery constraints

- communication latency

- wind and localization drift

Tools like a “SwarmGPT” concept make sense because human choreographers tend to think in narratives—“form a spiral, pulse to the beat, transition into a logo”—while the swarm needs explicit, constraint-satisfying trajectories.

Industrial parallels: warehouses and yards are swarms too

Swap drones for autonomous mobile robots (AMRs) in a fulfillment center, and the problem rhymes. You’re still doing multi-agent coordination under constraints.

Where LLMs can help (when implemented carefully):

- Rapid scenario setup: Describe operational goals (“prioritize outbound lane 3 until 2pm”) and generate policies.

- Exception handling: Translate messy human reports into structured tickets and rerouting suggestions.

- Operator interfaces: Let supervisors ask “why is zone C backed up?” and get interpretable explanations.

But here’s the non-negotiable: language models shouldn’t be the safety layer. They can author plans; deterministic constraint checkers and certified controllers should enforce limits.

Humanoids need differentiation—because “walking” isn’t the product

Answer first: Humanoid robotics companies will win by shipping specific, measurable capabilities (throughput, uptime, safety, total cost) rather than general-purpose promises.

A line in the roundup about companies realizing they need to differentiate is dead-on. The market is getting crowded. More importantly, buyers are getting more skeptical.

The question buyers actually ask

It’s not “Can it do a backflip?” It’s:

What useful, practical things can it reliably and cost-effectively and safely do?

If you’re on the buyer side, insist on answers framed in operations:

- cycle time per task

- pick success rate

- recovery behavior after failure

- maintenance intervals

- integration time with existing WMS/MES

- safety operating modes with humans nearby

A reality check on hands and tasks

Most near-term humanoid value comes from tasks like:

- tote and case handling

- cart and bin transport

- basic kitting

- simple machine tending

- inspection and patrol with mobile perception

Those tasks don’t demand a perfect human hand. They demand:

- robust grasping under variation

- fast perception in clutter

- safe motion planning near humans

- uptime that makes finance comfortable

If the end effector can’t survive the floor, the rest doesn’t matter.

Robotics isn’t just factories: mushrooms, microsurgery, and Mars

Answer first: The most exciting robotics trend is cross-industry spillover—hardware, perception, and control methods moving between manufacturing, healthcare, research, and space.

A few items in the roundup make the point in very different ways.

Altered gravity experiments with robot arms

Using an industrial robot arm to simulate altered gravity for biological experiments (like mushroom growth) shows how general-purpose robotics platforms are becoming research infrastructure. If you can program motion precisely and repeatably, you can build experiments that were previously expensive or impossible.

This spills back into industry: the same motion control and repeatability that helps a lab study biology also improves adhesive application, dispensing, inspection, and metrology.

VR-scaled microsurgery and “walking across the retina”

The University of Michigan project idea—scaling tissue so surgeons can operate in VR as if performing large motions—points toward a future where robotics, perception, and XR combine to make delicate procedures more controllable.

Even if you never touch healthcare, pay attention: medical robotics forces teams to solve hard problems in precision, safety, and human-machine interfaces. Those solutions tend to migrate into industrial robotics over time.

Space robotics is still the ultimate reliability test

Mars sample processing systems exist in a world where “send a technician” isn’t an option. That mindset—designing for autonomy, fault tolerance, and degraded modes—should inform terrestrial automation too.

When you’re planning AI and robotics transformation programs, steal this idea from space systems:

- define what “graceful failure” looks like

- design for remote diagnosis

- treat recovery as a primary feature, not an afterthought

Practical checklist: choosing robots that will survive deployment

Answer first: Evaluate robotics systems by durability, recoverability, and integration—not by human likeness.

Use this checklist in vendor conversations and pilot planning:

- End effector reality

- What objects, weights, and surface types are supported?

- What’s the plan for drops, impacts, and mis-grasps?

- Recovery behavior

- After a fault, does the robot self-reset, or does a technician intervene?

- Can it detect “I’m stuck” and request help safely?

- Human interaction

- Can a worker pause/guide/resume safely without special tools?

- How does touch or contact get interpreted?

- Integration time

- How many days to integrate with WMS/MES/PLC systems?

- What data do you get (events, error codes, utilization)?

- Cost realism

- What’s the expected maintenance spend per quarter?

- What consumables exist (pads, suction cups, belts, calibrations)?

If a vendor can’t answer these cleanly, you’re not looking at a deployment-ready platform.

Global momentum: the events calendar is a signal

Answer first: Major robotics events in 2025—like the World Robot Summit and IROS—are where industrial buyers can benchmark maturity, not just novelty.

The calendar mentions global gatherings in Japan and China in October 2025. Even though we’re closing out 2025 now, these events reflect an ongoing reality: robotics progress is increasingly international, and supply chains, research talent, and deployments are distributed.

If you’re building a 2026 roadmap, treat conferences and competitions as more than marketing:

- watch for repeatable benchmarks (grasping, navigation, recovery)

- look for integrator partnerships, not only hardware reveals

- pay attention to boring topics like safety cases, tooling, and maintenance

Those “boring” parts are where industry transformation actually happens.

What this means for AI & robotics strategy in 2026

Primary keyword, plain statement: robot grippers for humanoid robots are becoming a litmus test for who’s building for real work versus who’s building for videos.

If you’re leading automation—whether in manufacturing, logistics, healthcare, or research—optimize for systems that can take a hit, recover, and keep producing. Pair that with AI where it earns its keep: perception, planning, operator interfaces, and diagnostics.

If you want help mapping these trends to your environment (task selection, ROI modeling, pilot design, or vendor evaluation), we can translate “cool robotics” into an implementation plan your operations and finance teams will actually sign off on. What’s the one task in your operation that’s still too manual, too inconsistent, or too risky—and why hasn’t automation stuck yet?