Muscle-driven robot dogs and edge AI vision point to a new era of practical robotics. See what the latest demos mean for disaster response, healthcare, and automation.

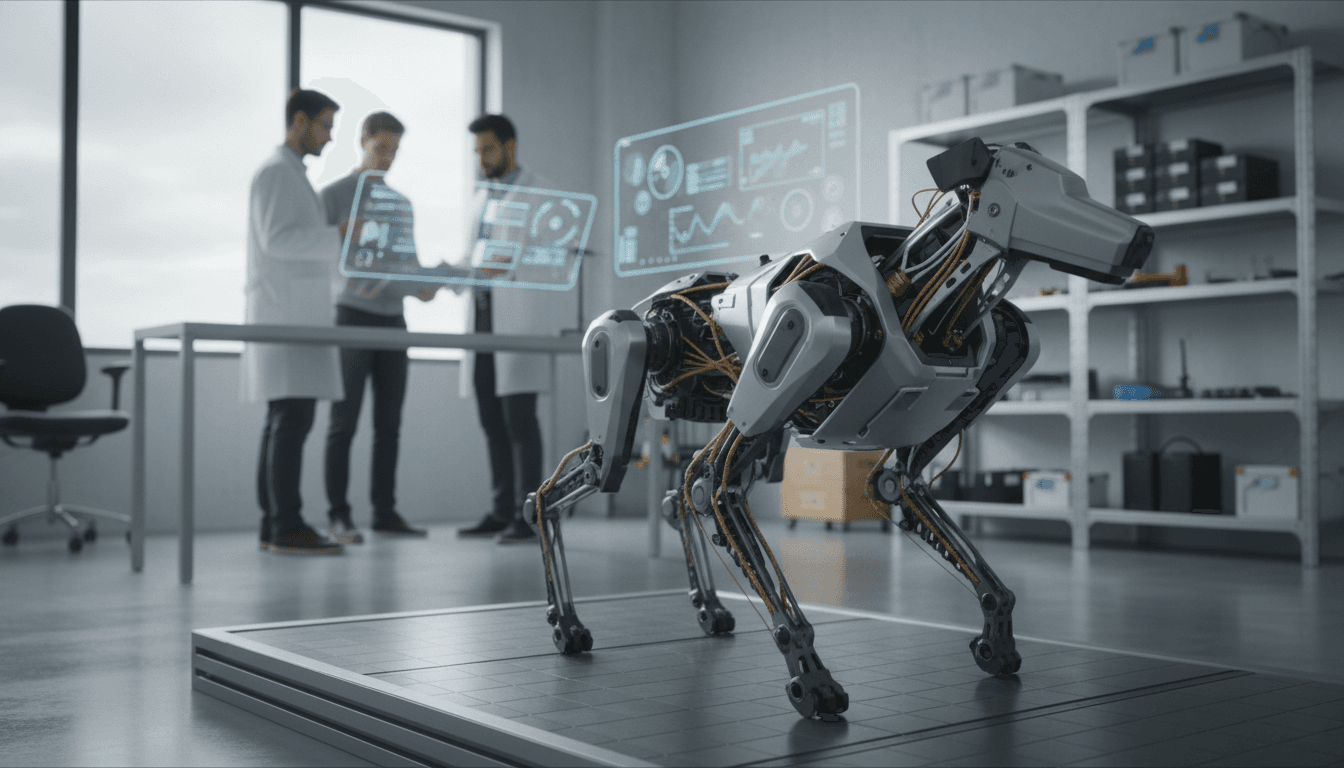

Robot Dogs With Muscles: AI Robotics Hits Real Work

A decade ago, most “robot dog” demos were basically a balance trick: a rigid machine staying upright while someone kicked it (usually for the camera). That era is ending. What’s showing up in labs right now—especially in the new musculoskeletal quadrupeds—signals a bigger shift: robots are starting to move like biological systems, and AI is finally getting bodies worth controlling.

This matters for anyone tracking how AI and robotics are transforming industries worldwide. Once robots can move with animal-like compliance, feel their way through contact, and adapt on-device, they stop being novelty platforms and start becoming reliable co-workers—in disaster response, healthcare, logistics, inspection, and manufacturing.

IEEE Spectrum’s latest “Video Friday” roundup is a good snapshot of the trend: a muscle-driven robot dog from Suzumori Endo Lab, speech-to-object robotic assembly from MIT, edge AI vision systems, soft wearable attachments, agile insect-scale flight, and safety-first autonomous driving. Put together, it reads like a preview of where automation is headed in 2026.

Musculoskeletal robot dogs: why “real muscles” change everything

A musculoskeletal robot dog is a big deal because it replaces rigid, motor-driven joints with compliant actuation that behaves more like animal tissue. Suzumori Endo Lab (Science Tokyo) built a dog-like robot using thin McKibben artificial muscles and a flexible, “hammock-like” shoulder structure inspired by canine anatomy.

That shoulder detail is not cosmetic. Dogs don’t have a collarbone anchoring the shoulder; their scapula “floats” in a sling of muscle. Translating that into robotics gives two industrial advantages:

- Passive shock tolerance. Compliant shoulders absorb impact when a robot lands, bumps, or slips.

- More forgiving contact. In the real world, robots constantly collide with soft, hard, and unknown surfaces. Compliance reduces damage and improves stability.

The control problem gets harder—and that’s the point

Soft actuation makes control more complex, but it also makes behavior more robust. Electric motors are easy to model; muscles (pneumatic or tendon-like) are not. Their behavior is nonlinear, temperature- and pressure-dependent, and often has hysteresis.

Here’s why I think that’s still the right direction: in industry, you don’t win by having the cleanest equations—you win by having the system that keeps working when the floor is wet, the load changes, and the environment is messy.

The most practical path is a hybrid stack:

- Biomechanics-inspired design (compliance, tendon routing, anatomical joints)

- Model-based control for stability and constraints

- Learning-based control for adaptation (terrain changes, payload shifts, wear)

If your company is evaluating quadrupeds for inspection or response work, “muscles” translate to a simple KPI: less time recovering from disturbances, and fewer failures from incidental contact.

Where muscle-like quadrupeds will show up first

Expect early adoption where falls and impacts are normal, and where humans currently accept risk. In practical terms:

- Industrial inspection: plants, tunnels, mines, substations

- Emergency response: rubble, smoke, stairs, wet surfaces

- Defense and security: perimeter patrol, remote sensing

- Research hospitals and rehab labs: gait research, patient interaction

Rigid quadrupeds can already do some of this. Musculoskeletal designs aim for a more valuable promise: do it while being safer around humans and more tolerant of unpredictable contact.

Disaster-response robot dogs: autonomy is moving on-device

The most important upgrade in field robots right now isn’t better walking—it’s better decision-making under uncertainty. Texas A&M engineering students showcased an AI-powered robotic dog aimed at disaster zones, using a custom multimodal large language model (MLLM) combined with visual memory and voice commands.

The industry implication is straightforward: robots are shifting from remote-controlled tools to semi-autonomous teammates. The “visual memory” piece is especially relevant—response robots don’t just need perception; they need continuity:

- What did I see in the last corridor?

- Which route was blocked?

- Where did I detect heat, gas, or a survivor?

A practical autonomy stack for real deployments

If you’re building or buying these systems, the stack that tends to work looks like this:

- Perception: RGB + depth + thermal (optional) + audio (optional)

- Local mapping and memory: spatial map plus semantic “notes”

- Task planning: constrained planning with human overrides

- Low-level control: stable locomotion and recovery behaviors

- Human interface: voice, tablet, or mission control with audit trails

MLLMs help most at the top—interpreting intent and summarizing the environment. But you still want deterministic safety layers underneath. A robot that talks well but falls badly is not a field robot.

Edge AI vision: the unglamorous bottleneck that decides ROI

Robotics lives or dies on perception latency and reliability. Luxonis’ pitch for the OAK 4 “edge AI” vision system (compute + sensing + 3D perception in one device) highlights a shift businesses should pay attention to: more inference is moving from the cloud to the robot.

Why it matters:

- Lower latency: faster reactions for navigation and grasping

- Higher uptime: less dependence on Wi‑Fi/LTE in warehouses or disaster sites

- Better privacy and security: fewer raw video streams leaving the site

- Predictable costs: fewer cloud inference spikes

If you’re trying to justify robotics spend, edge perception is where you can often pull the simplest lever: reduce failure rates by tightening the loop between sensing and action.

What to ask vendors about 3D perception

A lot of demos look great until lighting changes or reflective surfaces show up. Ask specific questions:

- What’s the depth sensing modality (stereo, ToF, structured light), and how does it fail?

- What happens in low light, glare, dust, fog, or rain?

- Can the robot keep operating when depth degrades (fallback behaviors)?

- Is the perception model updated and monitored, or shipped once and forgotten?

Those answers predict whether you’ll get a pilot that stays deployed.

“Speech to physical objects”: automation for non-experts

Turning natural language into manufactured objects is a direct attack on the biggest hidden cost in robotics: integration expertise. MIT presented a system that transforms speech into physical objects using 3D generative AI and discrete robotic assembly.

For industrial leaders, this points to a new workflow:

- Describe intent (“a small bracket that holds two cables apart”)

- Generate candidate designs

- Simulate fit and strength

- Assemble using modular parts or standardized primitives

This won’t replace mechanical engineering. It will, however, compress the time between idea and prototype, especially for fixtures, jigs, custom holders, and one-off aids on production lines.

Here’s the stance I’ll take: the first serious business win for generative AI in robotics won’t be humanoids—it’ll be faster tooling and faster iteration. That’s where lead times and downtime hide.

Soft robotics shows up where humans do: healthcare and handling

Soft mechanisms are steadily moving from “cool lab demo” to “workable product component.” Two examples from the roundup make that clear.

Vine-inspired grippers: safer handling without crushing

MIT and Stanford developed a robotic gripper inspired by vines—tendril-like structures that wrap around objects. This matters because many industries still struggle with grasping variance:

- Produce and food handling

- E-commerce items in flexible packaging

- Lab automation with fragile containers

- Assisted living and home care tasks

A gripper that wraps instead of pinches can reduce required perception precision. That’s a big deal: better hardware can lower software complexity.

Wearable robots: self-donning attachment is the real hurdle

A paper described an automatic limb attachment system using soft actuated straps and a magnet-hook latch for wearable robots, enabling fast self-donning across arm sizes, supporting clinical-level loads and precise pressure control.

In rehab and mobility tech, adoption often fails on practical details:

- Patients can’t put it on alone

- It takes too long to fit

- It’s uncomfortable after 20 minutes

Attachment systems sound mundane, but they decide whether an exoskeleton is a lab device or a daily tool. If you’re in healthcare innovation, invest in donning/doffing and comfort engineering early—it’s not “later work.” It is the work.

Agile microrobots and safe autonomous driving: AI meets physics

Two domains prove the same point: intelligence only counts when it survives real-world dynamics.

- MIT’s aerial microrobots achieved fast, agile insect-like flight using an AI-based controller capable of complex maneuvers like continuous flips.

- Waymo emphasized “demonstrably safe AI” in autonomous driving—building safety into models and the broader AI ecosystem.

These are wildly different systems, but the lesson transfers to industrial robotics: you need AI that is testable, monitorable, and bounded by safety constraints.

If you’re deploying AI-powered robotics at scale, borrow the autonomy playbook that’s emerging from self-driving:

- Define operational design domains (ODDs): where the robot is allowed to operate

- Instrument everything: near-misses, recovery events, perception failures

- Use staged rollouts: simulation → controlled site → limited hours → full ops

- Treat updates like safety-critical releases, not app patches

That’s how you keep automation from becoming a perpetual pilot.

What this means for business leaders planning 2026 pilots

The opportunity isn’t “buy a robot dog.” The opportunity is building adaptive automation that holds up in messy environments. The videos highlight three shifts that affect budgets and timelines immediately:

- Bodies are getting compliant. Muscles, soft grippers, and flexible structures improve robustness.

- Brains are getting contextual. Memory + multimodal models improve autonomy and usability.

- Perception is moving to the edge. Lower latency and higher reliability increase ROI.

A simple checklist for selecting AI-powered robotics

If you’re scoping pilots in 2026 (inspection, warehouse automation, healthcare robotics, or response), use this checklist to avoid the common traps:

- Define success in numbers: response time, uptime, items/hour, incidents avoided

- Ask for failure demos: show recovery from slips, occlusion, lighting changes

- Prioritize maintainability: battery swaps, sensor cleaning, field calibration

- Demand safety documentation: constraints, audits, update policies

- Plan the human workflow: who supervises, who intervenes, who owns the logs

A robot that’s 5% less impressive in a demo but 30% easier to operate is the one that gets renewed.

Where this series is headed—and what to do next

Robot dogs with muscle-like actuation are a signal that AI robotics is maturing from “controlled tricks” to “adaptive work.” Combine that with edge AI vision, safer autonomy practices, and practical advances in soft robotics, and the direction is clear: more industries will adopt robots not because they look impressive, but because they’re finally tolerant of the real world.

If you’re leading operations, innovation, or IT/OT integration, now is the right time to map which workflows are held back by three pain points: unsafe environments, repetitive handling, and unpredictable variation. Those are exactly the places these new systems are starting to shine.

What would your team automate first if the robot could recover from mistakes—rather than requiring a reset every time something unexpected happens?