Human-AI feedback loops shape culture and risk. Learn how Wiener's 1950 ethics map to AI governance, robotics, and collaboration in industry.

Human-AI Feedback Loops: Ethics Wiener Got Right

Seventy-five years is a long time in technology—and a short time in ethics. Norbert Wiener published The Human Use of Human Beings in 1950, and the best parts of his message still land with a thud on the conference-room table: when you build a machine that responds to people, you’re building a feedback loop that shapes people back.

Paul Jones’s poetic rereading of Wiener (the lines about “feedback loops of love and grace,” machines as mirrors, and the uneasy “spider” in every web) isn’t just a literary moment. It’s a practical lens for leaders deploying AI and robotics in manufacturing, healthcare, logistics, retail, and smart cities. Because most companies still treat AI like a tool you purchase and “roll out.” The reality is messier: AI becomes part of your organization’s nervous system. And whatever you wire into it—metrics, incentives, permissions, exceptions—will echo back into culture, customer experience, and risk.

Here’s how Wiener’s 75-year-old warnings and hopes translate into modern human-AI collaboration, AI governance, and real-world robotics in business.

Feedback loops are the real product (not the model)

The core point: AI systems don’t just make decisions; they create cycles. A recommendation changes behavior, which changes data, which changes the next recommendation. A robot changes workflows, which changes worker pacing, which changes safety risk and quality, which changes what gets optimized.

Wiener’s cybernetics was built on feedback—signals, response, correction. Jones reframes it with a human ask: can those loops carry “love and grace,” not just control? In industry terms, that means building systems that:

- Correct without punishing (e.g., coaching signals instead of automatic discipline)

- Optimize with constraints (quality + safety + fairness, not only throughput)

- Expose uncertainty (confidence and limits, not fake certainty)

What this looks like in factories and warehouses

In robotics deployments, the fastest way to create a toxic loop is to instrument only speed.

- If an autonomous mobile robot (AMR) program measures success as “picks per hour,” workers respond by rushing.

- Rushing increases near-misses and quality issues.

- Management reacts with tighter targets.

- The system becomes brittle—exactly what Wiener feared when control is treated as the only virtue.

A better loop measures balanced outcomes:

- Safety: near-miss rates, ergonomic load, traffic conflicts

- Quality: defects per batch, rework rates

- Flow: cycle time variability, downtime causes

- Human experience: training completion, task switching cost, fatigue proxies

Snippet-worthy rule: If you can’t describe your AI’s feedback loop in one sentence, you don’t control it—you’re just watching it happen.

Machines are mirrors: AI reflects your values at scale

Jones writes that with each machine “we make a mirror,” and that line should be printed on every AI steering committee agenda.

AI doesn’t magically import “intelligence.” It imports assumptions:

- What outcomes matter

- Who gets exceptions

- Which errors are tolerable

- What is considered “normal” behavior

That’s why AI ethics in industry is rarely about abstract philosophy. It’s about operational choices that harden into software.

Example: healthcare triage and the hidden mirror

In healthcare operations, AI triage can reduce waiting times and flag deterioration early. But the mirror shows up when:

- Historical data encodes unequal access to care

- “No-show” patterns correlate with transportation or job constraints

- Outcome labels reflect past under-treatment

If you train on that without correction, your “efficient” system becomes an accelerator for yesterday’s inequities.

Practical stance: If your AI is learning from history, you should assume it’s learning your organization’s blind spots too.

Mirror-check questions teams should ask

Use these in design reviews for AI and robotics programs:

- Whose work becomes easier, and whose becomes harder?

- Where does the system demand conformity? (Rigid workflows punish edge cases.)

- What happens when someone says “stop”? (Escalation paths are ethics in code.)

- Who can override the model—and who audits overrides?

These aren’t “soft” questions. They predict cost, downtime, churn, and compliance outcomes.

Unease is a signal: build governance that expects surprises

“Every web conceals its spider,” Jones writes—and the unease is justified. In modern AI terms, the spider is often:

- Hidden coupling (one model’s output becomes another model’s input)

- Vendor opacity (limited visibility into training data, evaluation, updates)

- Automation creep (pilot decisions gradually become policy)

AI governance gets dismissed as paperwork until an incident hits. Then it becomes the only thing anyone wants.

A governance approach that actually works in industry

Effective AI governance isn’t a binder. It’s a set of operational habits:

1) Treat models like changing machinery

Robots get preventive maintenance; AI needs the same mindset.

- Version models and prompts

- Log inputs/outputs with privacy safeguards

- Track drift and performance by segment (shift, site, customer type)

2) Define “freedom” as bounded discretion

Jones notes “freedom’s always a contingency.” In business: humans need room to deviate when reality doesn’t match the dataset.

- Provide a clear, non-punitive override path

- Make the system explain why it’s suggesting an action

- Require review thresholds for high-impact decisions

3) Set up incident response for AI and robots

If you already have safety and cybersecurity playbooks, extend them.

- What is a reportable AI incident?

- Who can pause automation?

- How do you communicate to frontline staff and customers?

Snippet-worthy rule: Governance isn’t there because you don’t trust your people; it’s there because you do—and you don’t want them trapped by automation.

“Commerce among us”: designing human-AI collaboration that people accept

One of the most useful phrases in the poem is “commerce among us.” Not domination. Not replacement. Exchange.

In the Artificial Intelligence & Robotics: Transforming Industries Worldwide series, this is the thread I keep coming back to: deployments succeed when they feel like a fair trade.

What “fair trade” looks like on the shop floor

If you want workers to trust robotics and AI systems, the deal can’t be “do more with less.” A workable deal is:

- The system takes the dangerous and repetitive tasks first

- People get training time built into schedules

- Metrics don’t quietly become punishment

- There’s a credible path to role growth (robot tech, cell lead, quality analyst)

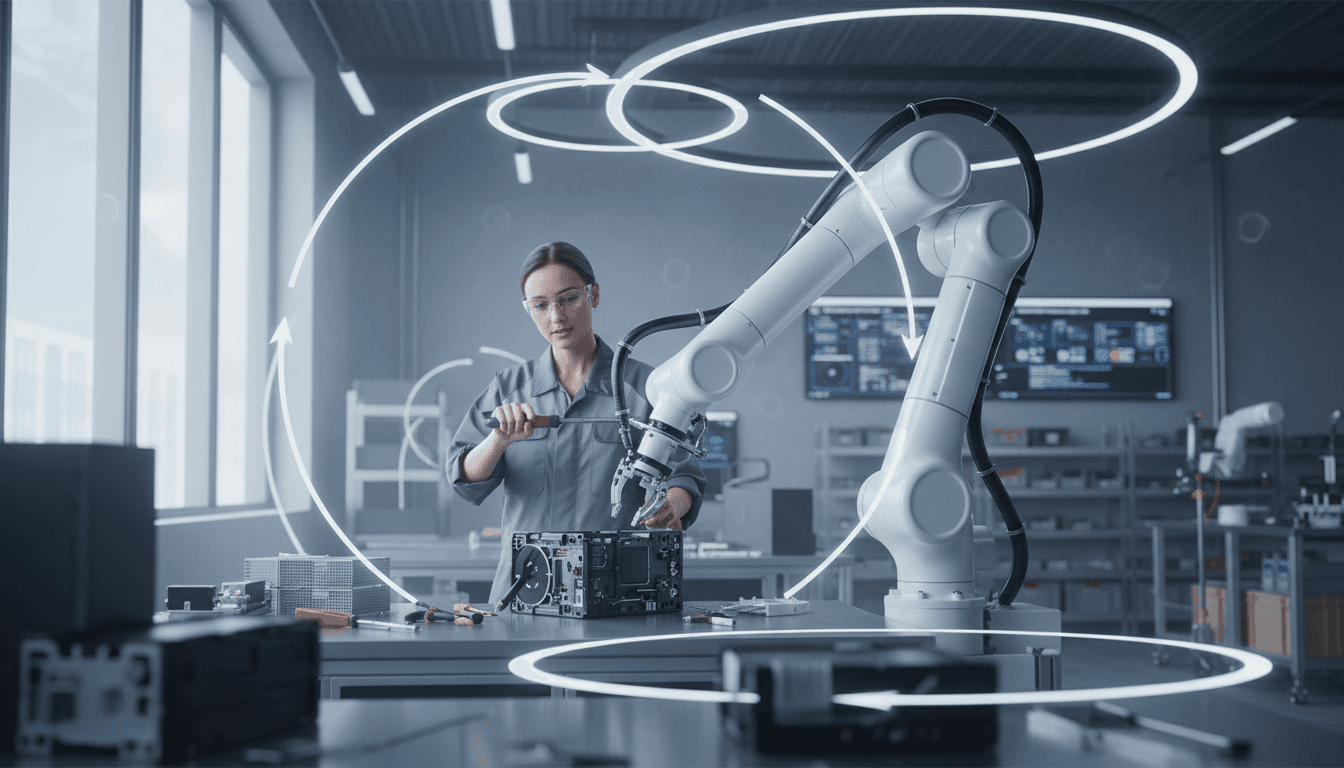

A concrete example: cobots and the dignity test

Collaborative robots (cobots) often start as assistive arms—holding parts, applying consistent torque, handling adhesives.

When cobots fail culturally, it’s usually not because the robot can’t do the job. It’s because:

- The line is rebalanced without worker input

- The cobot’s downtime becomes the worker’s blame

- The “helper” turns into surveillance (timing, micro-metrics)

Run a “dignity test” in your pilot:

- Does the automation reduce physical strain?

- Does it reduce cognitive load (fewer tricky steps)?

- Does it give workers more control over pacing?

If the answer is no, you’ve built a control loop, not a collaboration loop.

The better industrial playbook: grace by design

“Love and grace” can sound naive in an enterprise setting. I don’t think it is. In systems design, grace means the system is resilient when people are tired, new, distracted, or dealing with edge cases. That’s not sentiment. That’s operational excellence.

Here’s a practical playbook I’ve found works across AI-enabled operations:

1) Start with the failure modes, not the success demo

Before rollout, list the top 10 ways the system can fail:

- Wrong label / wrong location

- Sensor dropout

- Model confidence collapse on new SKUs

- Hallucinated instruction in a workflow assistant

Then design protections: rate limits, human confirmation, safe-stop behavior, and rollback.

2) Make feedback two-way

A cybernetic system needs signals from the environment. In human-AI collaboration, your environment includes people.

- Add “report this recommendation” buttons

- Allow workers to tag exceptions (“this aisle is blocked,” “this part is warped”)

- Treat that input as first-class data, not noise

3) Audit incentives as aggressively as you audit models

If bonuses depend on speed alone, no amount of “ethical AI” rhetoric will matter.

Align incentives to the outcomes you actually want:

- Safety incidents and near-misses

- First-pass quality

- Customer satisfaction

- Employee retention

4) Keep humans in the loop where stakes are high

Not every decision needs manual review. But in hiring, medical prioritization, credit, public safety, and high-risk industrial safety contexts, human oversight is non-negotiable.

A clean pattern is:

- AI suggests

- Human approves for high-impact cases

- System logs and learns from overrides

People also ask: what does Wiener have to do with AI in 2025?

He predicted the management problem behind the technology problem. Wiener understood that automation changes power: who decides, who is measured, who gets exceptions, and who pays for errors.

He also offered a hopeful constraint: if humans and machines are “old enough to be friends,” then the relationship has duties on both sides—design duties for builders, governance duties for operators, and dignity duties for employers.

That’s the standard worth carrying into 2026 planning cycles.

Next steps: turn your AI loop into a trust loop

If you’re leading AI and robotics adoption right now, treat this post as a checklist for your next steering meeting.

- Map the feedback loop end-to-end (data → model → decision → behavior → new data)

- Identify where control could become coercion (metrics, surveillance, exception handling)

- Add governance that expects drift, incidents, and overrides

- Define the “fair trade” for frontline teams in writing

The most profitable automation programs I’ve seen aren’t the ones with the flashiest demos. They’re the ones that earn cooperation—because the system behaves well under pressure.

Wiener asked what it means to use human beings humanely in an age of machines. The 2025 version is more specific: Will your AI and robotics program make your organization more rigid—or more capable of wise discretion when reality gets weird?