Flying humanoid robots like iRonCub could help in floods and fires by combining jet-powered access with hands-on manipulation. Here’s why it matters.

Flying Humanoid Robots for Disaster Response: iRonCub

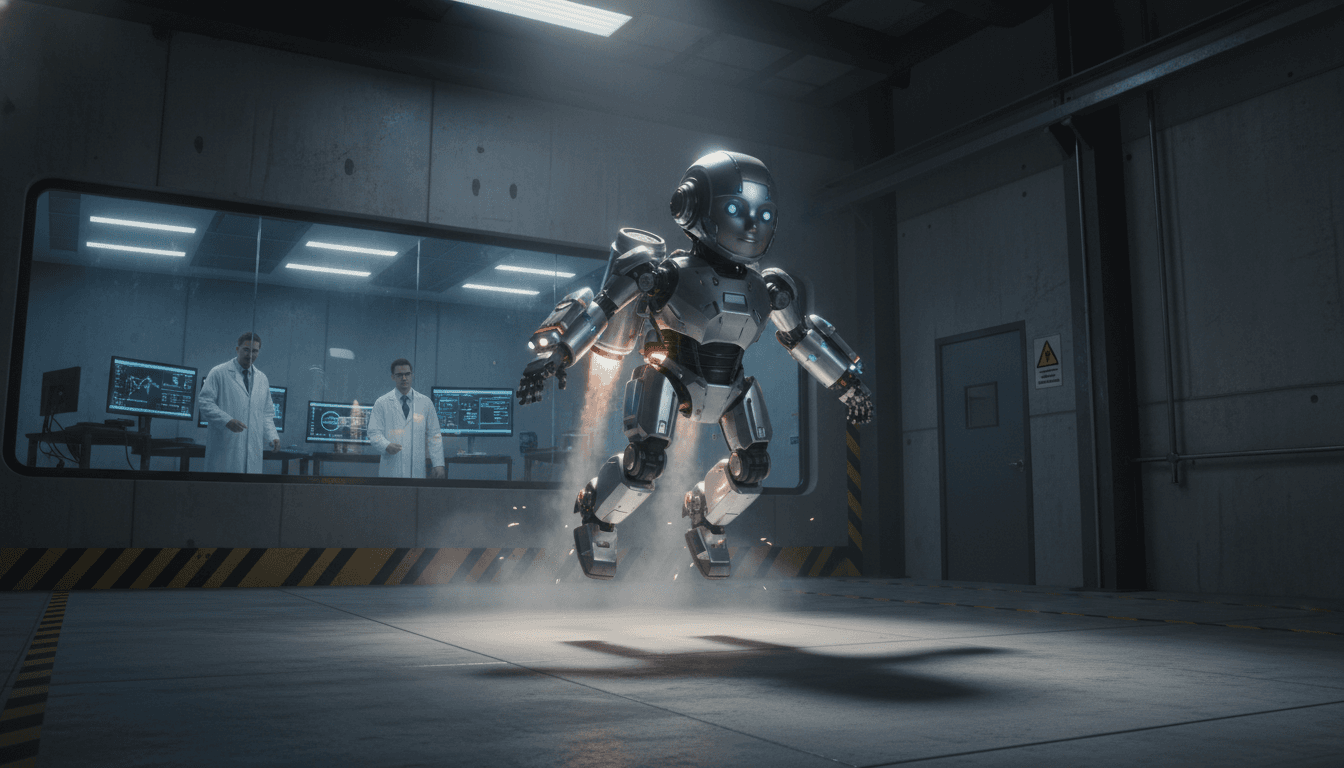

A humanoid robot in Italy just rose into stable flight—about 50 centimeters off the ground for several seconds—using four jet engines and a control system that has to react faster than the turbines can. That doesn’t sound like a practical product launch. It sounds like a science stunt.

Most companies get this wrong: they evaluate “flagship” robotics projects only by how close they are to immediate deployment. The better question is whether the project creates transferable capabilities—the kind that show up later in emergency operations, industrial automation, and autonomous mobility.

That’s why the world needs a “flying robot baby.” iRonCub (built on the child-sized iCub humanoid platform at the Italian Institute of Technology in Genoa) is less about cosplay and more about AI-driven flight control in a body that can land, walk, and use hands. In the broader Artificial Intelligence & Robotics: Transforming Industries Worldwide series, iRonCub is a clean example of how “weird” robotics R&D turns into tools that change real operations.

iRonCub in one sentence: fly over the mess, then work like a human

The simplest case for a flying humanoid robot is operational: disasters are obstacle courses. Floods, fires, earthquakes, collapsed buildings, industrial explosions—these environments punish wheeled robots and slow down legged ones.

A disaster-response humanoid that can take off, clear debris fields, cross water, and land precisely has a unique advantage: it can get to where humans can’t safely go, then switch to walking for efficiency and use hands for manipulation—opening doors, moving light debris, turning valves, carrying sensors, or placing radios.

Why not just use drones?

Drones already dominate search-and-assess tasks, and they’ll keep doing it. But drones struggle when the job becomes interactive.

A drone is great at:

- Mapping and thermal imaging

- Dropping small payloads

- Spotting people and hazards

A humanoid is better when you need:

- Two-handed manipulation (doors, latches, breakers, hoses)

- Tool use designed for humans (handles, knobs, levers)

- Physical presence on the ground for sustained tasks

The real insight is the combination: flight for access + humanoid manipulation for action. That pairing is rare—and strategically valuable.

The hard part isn’t thrust. It’s control under brutal physics

iRonCub’s turbines can generate over 1000 N of thrust, but thrust alone doesn’t buy stability. The biggest engineering constraint is that jet turbines don’t change thrust instantly—they spool up and down with delay. When your actuators respond slowly, your body has to do the fast corrections.

So iRonCub stabilizes by moving its arm-mounted engines, using the robot’s own motion to compensate while the turbines catch up. That’s a very different control problem than a quadcopter where motors respond quickly, or a walking humanoid where contacts with the ground dominate dynamics.

“The exhaust gas from the turbines is at 800 °C and almost supersonic speed.” —Daniele Pucci, IIT

Thermal and aerodynamic forces change the humanoid playbook

The turbine exhaust is hot enough to destroy nearby structures, and fast enough to create aerodynamic effects that most humanoids were never designed to handle.

This forces three practical innovations that matter beyond iRonCub:

- Trajectory planning that accounts for exhaust cones so the robot doesn’t cook itself (or the environment)

- Aerodynamic force modeling on a complex, irregular body (arms, torso, legs) rather than a smooth aircraft surface

- Hybrid AI + classical control for stability when the physics gets messy

The project’s published work on modeling and controlling aerodynamic forces for humanoids is a big deal because it treats wind, thrust wash, and body drag as first-class citizens. If you expect outdoor humanoids to do anything useful, you need that.

What this means for emergency operations in 2026 (and beyond)

A flying humanoid robot won’t be a first responder in the sense of replacing firefighters. The useful near-term frame is human-AI collaboration: robots extend reach, reduce exposure, and speed up the “first 30 minutes” when information and access are limited.

Here’s where flying humanoid robots fit best.

1) “Access first” missions: get eyes and sensors where teams can’t

In fast-moving disasters, incident commanders need answers:

- Is the stairwell intact?

- Is there heat behind that door?

- Are there hazardous gases near the valve bank?

A flying humanoid can potentially carry a sensor suite, land on a narrow platform, and place instruments rather than just observe.

2) Intervention missions: do small physical tasks that unblock humans

The highest ROI tasks are often boring:

- Opening or closing a door

- Clearing light debris from a pathway

- Turning a lever or breaker

- Pulling a fire door shut to slow smoke spread

These are exactly the tasks that are hard for drones and time-consuming (or dangerous) for people.

3) Mixed terrain in harsh conditions

Floodwater, rubble, mud, stairs, broken pavement. A robot that can skip the worst segments by flying and then conserve energy by walking is not a gimmick. It’s a logistics advantage.

The “flying robot baby” effect: tools built for iRonCub spill into industry

The part I find most convincing isn’t the flight demo. It’s what Daniele Pucci described as an “ah-ha” moment: methods developed for turbine force estimation ended up helping control a pneumatic gripper in an industrial collaboration.

That’s how robotics progress actually happens. A hard project forces you to build:

- Better estimators

- Better controllers

- Better simulation pipelines

- Better safety constraints

- Better sensing and calibration routines

Then those capabilities get reused in less flashy, highly profitable contexts.

Transfer #1: Directed-thrust estimation for eVTOL and industrial mobility

Algorithms that estimate thrust and compensate for delays are relevant to any platform with directed thrust—especially where safety margins are tight. That includes eVTOL-style systems and other advanced aerial robotics.

Transfer #2: Aerodynamic compensation for outdoor humanoid robots

If you want humanoid robots working outdoors—construction sites, ports, mining facilities, farms—wind isn’t a corner case. It’s constant. Robust aerodynamic modeling makes outdoor autonomy less fragile.

Transfer #3: Force estimation for manipulation (grippers, arms, compliant tools)

Force estimation is a universal robotics problem. If your control stack gets better at inferring forces under noisy conditions, you don’t just fly better—you grip, lift, and interact better.

What’s next: yaw control, wings, and the unglamorous reality of testing

Answer first: progress depends on better controllability and better test logistics, not just more thrust.

The team’s near-term upgrades point to where the pain is:

- A new jetpack with an added degree of freedom to make yaw control easier

- Potential wings for more efficient longer-distance flight

But the least talked-about constraint is operational: testing. Early experiments can happen on a rooftop stand. Real progress requires bigger flight envelopes, stricter safety procedures, and in this case potentially coordinating with local airport operations.

That tension—between ambitious robotics and the realities of safety and regulation—will shape every serious attempt to put flying robots into public-space emergency workflows.

Practical takeaways for leaders evaluating AI robotics projects

If you’re in emergency management, industrial safety, utilities, or critical infrastructure, the point isn’t to buy a jet humanoid next quarter. The point is to learn how to judge projects that look “too early” but create real strategic advantage.

Here’s a framework that works.

Evaluate the capability, not the demo

Ask:

- What new sensing, control, or estimation capability was proven?

- Can it be reused in ground robots, drones, or industrial manipulators?

- Does it improve performance under uncertainty (wind, heat, dust, smoke)?

Look for “deployment-adjacent” pilots

The fastest path to value usually isn’t full autonomy in chaos. It’s constrained environments:

- Training facilities for firefighters

- Industrial sites with established safety perimeters

- Ports, yards, and utilities with clear access control

Plan for human-AI collaboration from day one

A realistic operating model is:

- Humans set goals and safety constraints

- Robots execute bounded tasks and return structured data

- Command teams validate actions before escalation

That’s not a compromise. It’s how you build trust and reduce operational risk.

People also ask: is a flying humanoid robot actually necessary?

Yes—for specific tasks where access and manipulation both matter. A drone can’t reliably operate standard human interfaces. A ground humanoid can be blocked by terrain. A flying humanoid is the smallest category that can do both.

No—as a general replacement for responders. The near-term win is targeted missions that reduce exposure and speed up situational awareness.

Where this fits in the bigger AI and robotics transformation

Across industries worldwide, the pattern is consistent: the robotics systems that create the most value are the ones that handle edge conditions—the messy, dangerous, unpredictable moments that break traditional automation.

Flying humanoid robots like iRonCub sit right on that boundary. They force advances in AI-driven flight control, force estimation, and robust autonomy. Even if the final “Iron Man robot” isn’t the product you deploy, the control stack and modeling techniques are exactly the kind of industrial building blocks that show up later in safer factories, smarter eVTOL systems, and more capable field robots.

If you’re building an AI robotics roadmap for 2026, pay attention to projects like iRonCub. Not because they’re flashy—but because they pressure-test what robotics still can’t do well.

The forward-looking question is simple: when the next disaster hits, do we want robots that can only watch from above—or robots that can arrive, land, and start helping?