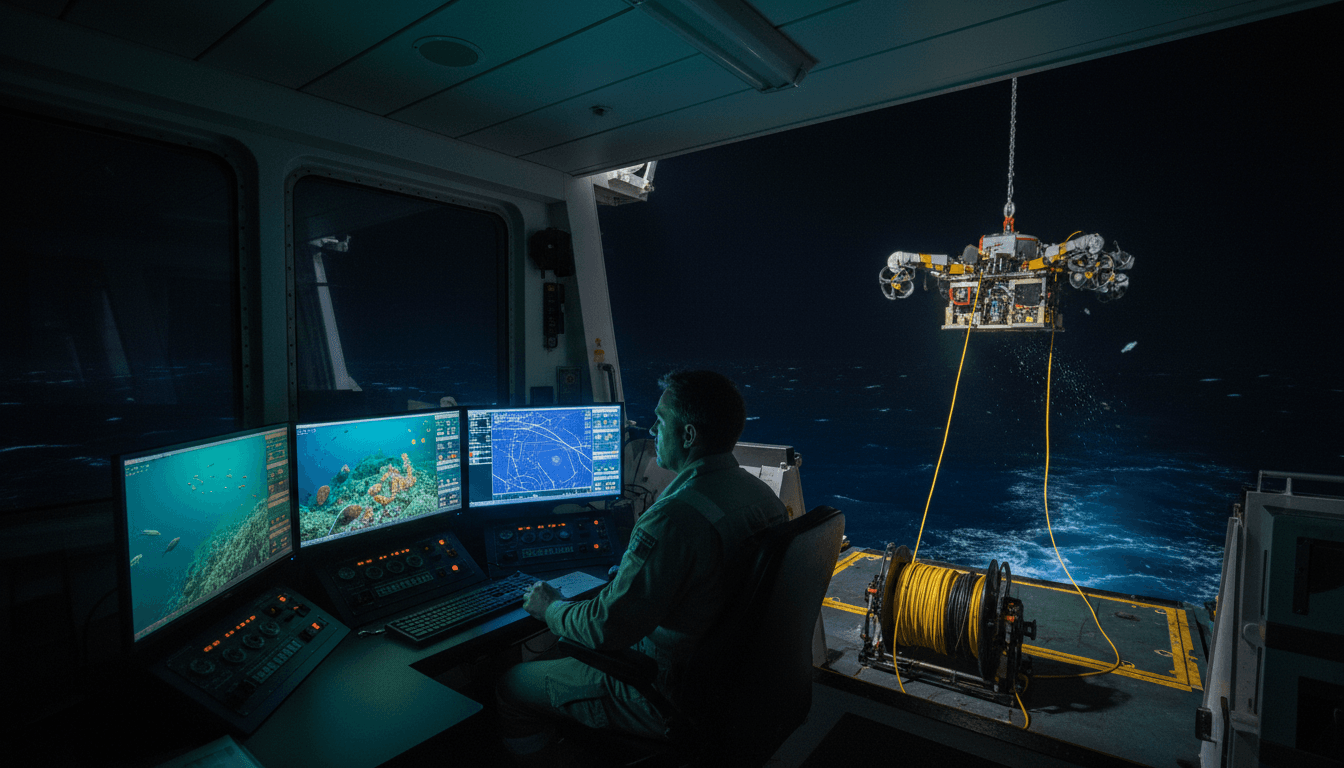

AI underwater robots push robotics to the limit. Learn what deep-sea ROV engineering teaches about edge AI, reliability, and human-machine teamwork.

AI Underwater Robots: Engineering for Deep-Sea Discovery

A deep-sea robot doesn’t fail politely. When something goes wrong a few kilometers below the surface, you’re dealing with crushing pressure, limited bandwidth, and a ship that can’t exactly “run to the store” for parts. That’s why the most useful lens for understanding underwater robotics isn’t sci-fi—it’s systems engineering under extreme constraints.

Levi Unema’s career arc captures that reality. He went from factory automation and industrial robotics to building and piloting remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) for scientific expeditions with NOAA. When the nonprofit team he worked with lost its contract in mid-2025, he and colleagues formed a new consultancy—Deep Exploration Solutions—to keep these robots operational and evolving. The story isn’t just personal. It’s a clear snapshot of how AI and robotics are transforming industries worldwide, even in places where GPS doesn’t work and humans can’t go.

What follows is the practical takeaway: what deep-sea ROV engineering teaches any organization building AI-powered robotics for harsh, high-stakes environments—energy, manufacturing, mining, defense, infrastructure, and beyond.

Deep-sea ROVs are “real robotics,” not demos

Deep-sea ROVs are a high-pressure proof test for robotics because they combine mechanical design, electronics packaging, sensing, networking, and human-in-the-loop control in one machine. If your robotics strategy assumes clean labs, reliable Wi‑Fi, and easy maintenance access, deep-sea work is the antidote.

Unema’s background matters here. Before ocean exploration, he worked in manufacturing systems and industrial robotics—exactly the kind of environment where uptime, safety, and repeatability are non-negotiable. That mindset translates directly to scientific ROV operations:

- You don’t “ship features.” You ship reliability.

- You don’t optimize one subsystem. You optimize the vehicle as a whole.

- You don’t treat operators as an afterthought. You design around them.

Scientific ROVs are also different from the heavier-duty vehicles used in oil and gas. They’re often hand-built, instrument-heavy, and tuned for smooth, precise motion so scientists can observe fragile ecosystems, approach corals without blasting them with thruster wash, and position cameras for hours.

A useful rule: the more your robot exists to observe and decide, the more you’re building an information system—not just a machine.

That’s where AI shows up—not necessarily as a fully autonomous pilot, but as the layer that helps teams interpret data, manage sensors, and make better decisions faster.

The engineering constraints that force better robotics

A lot of AI and robotics talk focuses on algorithms. Deep-sea work forces the uncomfortable truth: physics and packaging decide what’s possible.

Pressure turns electronics into a packaging problem

At depth, pressure is relentless. Many electronics can’t survive it directly, so they’re placed inside pressure housings—often titanium cylinders. Unema describes the constant trade-offs between size, weight, and cost:

- Smaller pressure cylinders cost less and weigh less.

- Less weight reduces buoyancy requirements (and the size of flotation).

- Tight spaces force careful PCB layout, connector choices, and thermal planning.

This is the kind of constraint that makes teams better. You stop adding sensors casually. You stop tolerating sloppy wiring. You build with serviceability in mind because repairs happen on a ship, not a bench.

Bandwidth is limited, even with fiber

NOAA-class scientific ROVs can run several kilometers of tether, often with only a few optical fibers carrying everything—video, telemetry, control signals, sonar data, and whatever new instrument the science team adds this season.

Unema’s point is blunt: every year, new instruments consume more data. That’s a universal robotics problem now—whether you’re running a warehouse fleet or inspecting pipelines. Sensors multiply faster than bandwidth.

Practical implications (and where AI fits):

- Edge computing becomes mandatory. You compress, filter, and prioritize onboard.

- Event-driven capture beats “record everything.” AI can flag anomalies worth streaming.

- Data products matter. Instead of raw feeds, deliver summaries: detections, tracks, mosaics.

Operations at sea demand “field-repairable” robotics

On expeditions, Unema pilots the robot while scientists watch camera feeds and call targets—corals, sponges, deepwater creatures, geological features. It’s a high-trust human-machine workflow.

But the underrated part is maintenance under constraints:

- You’re remote—often in the middle of the Pacific.

- Spares are limited.

- Time is expensive.

This pushes teams toward modular design and disciplined test routines: pre-dive checklists, sensor health checks, redundancy where it matters, and “good enough” fixes that keep a mission going.

Human + AI + robotics: the real operating model

The popular narrative is full autonomy. The operational reality—especially in science—is human-led exploration with machine execution, increasingly assisted by AI.

Here’s what that looks like in practice.

Human-in-the-loop control is a feature, not a limitation

In deep-sea missions, decisions are collaborative:

- The science team interprets what they’re seeing and decides what matters.

- The ROV pilot translates intent into motion—steady, precise, safe.

- The robot extends reach with sensors, lighting, cameras, sonar, and manipulators.

AI strengthens this model by reducing cognitive load:

- Computer vision can tag organisms, classify habitats, or detect “interesting” frames.

- Assisted piloting can stabilize hover, maintain distance to terrain, and manage thrusters.

- Predictive maintenance models can catch a failing connector or degrading motor before it ruins a dive window.

You don’t need full autonomy to get major value. In fact, in messy environments, partial autonomy tends to deliver faster ROI because it improves safety and throughput without asking stakeholders to trust a black box.

The best robotics teams build workflows, not just robots

Unema’s role spans idea → design → build → operations. That’s a clue: deep-sea robotics works because the same people who wire the system also watch it behave under real conditions.

If you’re building AI-powered robotics in any industry, copy this loop:

- Design with operators (and keep them involved after deployment).

- Instrument everything (logs, health metrics, fault codes).

- Review every mission/run like an incident postmortem, even when it succeeds.

- Ship improvements in the offseason (or planned downtime), not ad hoc.

This is how you go from “robot that can move” to robotic system you can depend on.

What deep-sea robotics teaches other industries

The ocean is an extreme environment, but the lessons transfer cleanly to industries adopting AI and robotics at scale.

1) Reliability beats novelty

A robot that works 92% of the time is not “almost done” when each failure costs hours of downtime, lost opportunity, or safety risk. Deep-sea ROVs push teams toward fault tolerance and disciplined testing.

Actionable move: define reliability targets like you would for manufacturing:

- Mean time between failures (MTBF)

- Mean time to repair (MTTR)

- Recovery behavior (what happens on partial failure?)

2) Edge AI is a business requirement

When bandwidth is constrained or latency is unacceptable, edge AI isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s the difference between usable and unusable data.

Actionable move: create a sensor-data budget:

- Which streams must be real-time?

- Which can be sampled?

- Which can be summarized by onboard AI?

3) Modularity is how you survive the real world

Scientific ROVs evolve constantly—new cameras, sonars, samplers, science payloads. If integration is painful, innovation slows.

Actionable move: standardize interfaces:

- Power rails

- Data buses

- Mechanical mounting

- Environmental sealing standards

4) Talent pipelines matter more than most teams admit

Unema got recruited through a teacher and mentor network—then built expertise through hands-on ops. Ocean robotics is a small community, and that’s true of many robotics niches.

Actionable move: if you want to scale robotics, build your pipeline now:

- Internships tied to real missions

- Rotations between design and operations

- Mentorship programs that reward knowledge transfer

If you’re considering an underwater robotics program, start here

Organizations exploring underwater robotics—ports, offshore wind, aquaculture, environmental monitoring, defense—often jump straight to vehicle selection. Start with mission design.

A practical checklist for scoping underwater ROV work

- Mission type: inspection, mapping, sampling, monitoring, recovery

- Depth & duration: defines pressure rating, power, and tether requirements

- Sensor suite: video, lighting, sonar, navigation, manipulators

- Data plan: what must be streamed vs stored; who analyzes what

- Ops model: ship time, crew training, maintenance windows

- AI opportunities: detection, segmentation, change detection, anomaly alerts

If that list feels heavy, good. Underwater robotics is unforgiving, and the teams that win are the ones who treat it like an end-to-end system from day one.

Where this fits in the bigger AI & robotics story

In our Artificial Intelligence & Robotics: Transforming Industries Worldwide series, the through-line is consistent: robots create value when they’re deployed into real workflows, under real constraints, with humans who trust them.

Levi Unema’s path—from industrial automation to deep-sea exploration—shows why. The tech is advanced, but the differentiator is the same one you see in warehouses, hospitals, and factories: the teams that succeed are the ones who can design, operate, and improve systems in the field.

If you’re building AI-powered robotics products—or you’re buying them—ask yourself one forward-looking question: Are you investing in a robot, or in an operating capability that gets better every month?