AI-powered robots now walk, fly, drive, and manipulate heavy loads. See what this means for scalable automation across logistics, cities, and industry.

Robots That Walk, Fly, and Drive: What’s Next

A tire weighs 15 kilograms (33 pounds). That’s not an internet “fun fact”—it’s the difference between a robot doing a cool demo and a robot doing paid work. When Boston Dynamics’ Spot heaves, steadies, and manipulates that kind of load autonomously, you’re seeing the real bottleneck in AI-powered robotics: reliable physical intelligence.

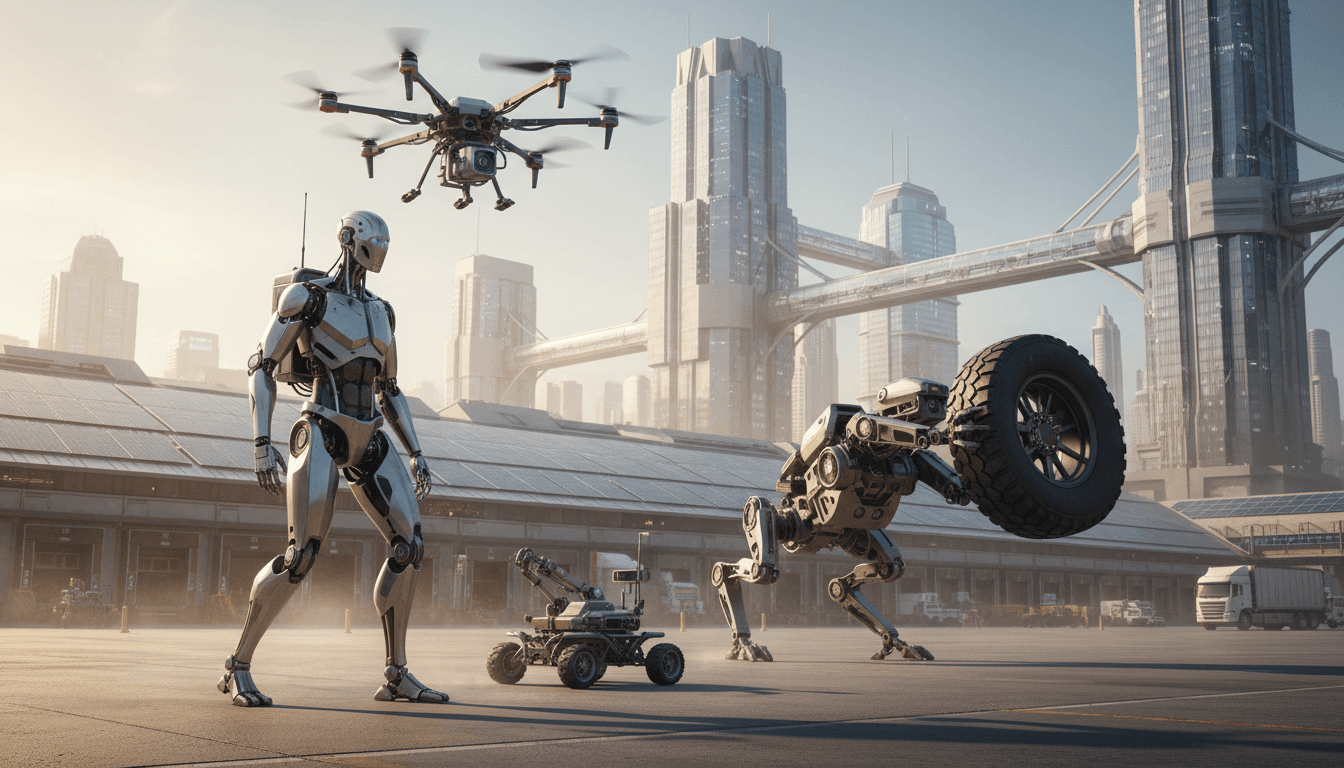

This week’s robotics video roundup is a tidy snapshot of where the industry is heading as we close out 2025: robots that switch modes (humanoid-to-drone-to-rover), quadrupeds that manipulate like mobile arms, humanoids designed for manufacturing scale, and research that’s quietly solving the hardest parts—contact planning, tactile reasoning, and pose control.

For leaders tracking the “Artificial Intelligence & Robotics: Transforming Industries Worldwide” trendline, the point isn’t that robots can do flips and tricks. The point is that mobility and manipulation are converging, and that convergence is what turns robots from niche automation into general-purpose systems that can move materials, support technicians, and operate across warehouses, hospitals, campuses, and construction sites.

Multimodal robots are the blueprint for smart cities and field work

Multimodal robotics matters because real environments don’t cooperate. A robot that can only walk fails at stairs, gaps, and long distances. A robot that can only fly struggles with endurance and payload. A robot that can only drive gets stuck when the terrain changes. The practical solution is mode switching.

A standout example comes from Caltech’s Center for Autonomous Systems and Technologies (CAST) and the Technology Innovation Institute (TII) in Abu Dhabi: a multirobot demo where M4 launches in drone mode from a humanoid’s back, lands, converts into driving mode, then returns to drone mode as needed. It’s a clear signal that the next wave of autonomous systems won’t be “one robot, one job.” It’ll be systems-of-systems, designed for coverage, redundancy, and task flexibility.

Where multimodal autonomy pays off first

I’m bullish on multimodal robots in three near-term industry use cases:

- Infrastructure inspection at scale: Fly to reach elevated assets (bridges, towers), drive for long corridors (pipelines, rail), and use a humanoid or mobile manipulator when a physical action is needed (turning a valve, placing a sensor).

- Logistics yards and campuses: Driving handles distance; flying handles urgent exceptions and scanning; walking or manipulation handles the “last meter” of physical interaction.

- Disaster response and remote operations: Mode switching reduces the need to deploy multiple platforms with different crews, which is exactly what you don’t have time for during an emergency.

The deeper takeaway: global collaboration is now part of the product roadmap. The Caltech–Abu Dhabi partnership isn’t just academic goodwill. It’s a model for how robotics is being industrialized—talent, compute, hardware, and field testing distributed across borders.

Whole-body manipulation is the capability most companies underestimate

The fastest way to spot a “lab demo” is when the robot only uses the gripper. Industrial environments don’t work that way. Real tasks require bracing, leaning, counterbalancing, and sometimes using the body like a second hand.

In the Spot manipulation work from the Robotics and AI Institute, the robot performs dynamic whole-body manipulation using reinforcement learning plus sampling-based control. The system autonomously chooses contacts across the arm, legs, and body—and coordinates manipulation with locomotion. That matters because once payload mass becomes significant (like that 15 kg tire), stability becomes the job.

There are two very practical implications for AI-powered robotics deployments:

1) “Manipulation” is really a contact-planning problem

Warehouses, factories, and back-of-house retail are full of awkward interactions:

- Holding a part steady while another tool engages it

- Sliding or pivoting loads that are too big to lift cleanly

- Bracing against a shelf or cart to avoid tipping

These aren’t edge cases. They’re the daily reality of material handling. Whole-body control is what lets a robot work at human sites without demanding the site be rebuilt around the robot.

2) Autonomy still depends on perception and compute economics

The demo uses external motion capture to simplify perception and external compute over Wi‑Fi for heavy processing. That’s not a knock—it’s an honest snapshot of where the stack is.

If you’re planning a robotics program in 2026, ask vendors two blunt questions:

- What happens when the robot loses network connectivity for 30 seconds?

- What’s the minimum sensor setup to achieve the advertised autonomy in your environment?

Most robotics deployment failures aren’t about the robot’s arm strength. They’re about perception drift, network assumptions, and incomplete integration planning.

Humanoid robots are shifting from prototypes to products—carefully

Humanoids are getting serious, but “serious” doesn’t mean “ready for every home.” The hype cycle often frames humanoids as universal labor. The reality is narrower and more useful: humanoids are attractive because they can operate in spaces designed for humans—doors, carts, shelves, stairs—without a full facility redesign.

The messaging around Figure 03 emphasizes mass-manufacturing readiness, tactile intelligence, and home-safe design. Whether any single model wins the category is less important than the direction of travel: companies are building humanoids as platforms—hardware plus an AI learning stack—aimed at both commercial and domestic settings.

Here’s my stance: humanoids will scale first in controlled commercial environments, not living rooms. The risk profile is lower, supervision is easier, and tasks are easier to standardize.

Where humanoids will show ROI sooner than people expect

Look for early wins in jobs that are physically repetitive but operationally variable:

- Kitting and line feeding in manufacturing

- Returns processing in e-commerce (high variability, high volume)

- Night shift facility support (moving supplies, basic checks, escorting payloads)

And yes—some demo clips with kids, pets, and humanoids make me nervous too. If you’re buying robots, build your safety case around the real environment, not the staged one.

Shape-shifting materials and robot “bodies” will change the design rules

Most robotics roadmaps assume rigid links and joints. Soft and morphing materials break that assumption. Researchers at the University of Bristol demonstrated early work using electro-morphing gel (e-MG) that enables shape-shifting behaviors—bending, stretching, and reconfiguring through electric fields and ultralight electrodes.

This is preliminary, but the industrial implications are huge:

- Safer human-robot interaction: compliant bodies reduce pinch points and impact forces.

- Better grasping: shape adaptation can replace complex grippers in some scenarios.

- Resilience: deformable structures can tolerate bumps and misalignment that would stall rigid robots.

A useful way to think about it: traditional robots solve uncertainty with sensing and planning. Morphological computation solves some uncertainty with the body itself.

Dynamic movement is cool—dynamic reliability is what gets budgets approved

Yes, we’re seeing “peak dynamic humanoid” style clips, but the real frontier is repeatability. Dynamic manipulation research like “throw-flipping” (throwing objects to land at a desired position and orientation) is a great example. Logistics doesn’t just need a box to land somewhere—it needs the label facing up, the part aligned for the next machine, or the item oriented for packing.

If you want a practical interpretation for industry: dynamic actions reduce cycle time, but only if the downstream process can trust the outcome.

A simple rule for evaluating impressive demos

When you watch a robotics video and wonder “is this deployable,” look for these signals:

- Multiple consecutive runs without resets or hidden edits

- Variation in objects and starting conditions, not one tuned scenario

- Clear failure handling (robot detects error, recovers, retries)

Reliability is a product feature. If it isn’t shown, assume it’s not solved.

What business leaders should do with this information (December 2025 playbook)

Robotics is shifting from single-task automation to adaptable fleets. That’s great news, but it changes how you should buy, pilot, and scale.

If you’re exploring AI-powered robotics in 2026

Start with a narrow pilot, but design it like a real deployment. Here’s what works:

- Pick a task with measurable throughput (items moved per hour, picks per shift, inspection coverage per day).

- Instrument the environment early (markers, RFID, structured storage) to avoid blaming the robot for missing infrastructure.

- Budget for integration (APIs, WMS/MES hooks, safety reviews, training). Integration is often 30–50% of effort.

- Plan for human workflows: robots succeed when humans know how to hand off, override, and escalate.

If you already have robots in production

Your biggest upside is usually not buying a new robot—it’s expanding capability:

- Add whole-body manipulation tasks (push, brace, pivot) rather than only lifting.

- Move from fixed routes to exception handling (the messy 10% of cases).

- Use robots to generate better operational data: where delays occur, where damage happens, where rework repeats.

Practical one-liner: The ROI comes from reducing variability, not from chasing maximum speed.

The bigger story: robotics is becoming a global industrial layer

The most interesting pattern across this week’s videos isn’t any single machine. It’s the stacking of capabilities: multimodal mobility, whole-body control, tactile learning, dynamic manipulation, and materials that change what “a robot body” can be.

That’s why the “Artificial Intelligence & Robotics: Transforming Industries Worldwide” series matters right now. Robotics is no longer confined to a few high-volume manufacturing lines. It’s spreading into logistics, facilities, inspection, and public infrastructure—places where adaptability matters as much as accuracy.

If you’re deciding where to place bets, treat the walk/fly/drive spectacle as a signal—not a gimmick. The signal is that general-purpose robotics is being built from the outside in: first mobility, then manipulation, then safe operation around people, and finally scalable production.

The next 12 months will reward teams that ask sharper questions than “can it do the demo?” The better question is: can it do the job on a bad day, in a messy environment, with humans nearby?