NGK’s shutdown of its NAS sodium–sulfur batteries is a wake‑up call for long‑duration storage. Here’s what it means for lithium rivals, LDES economics and AI‑driven green tech.

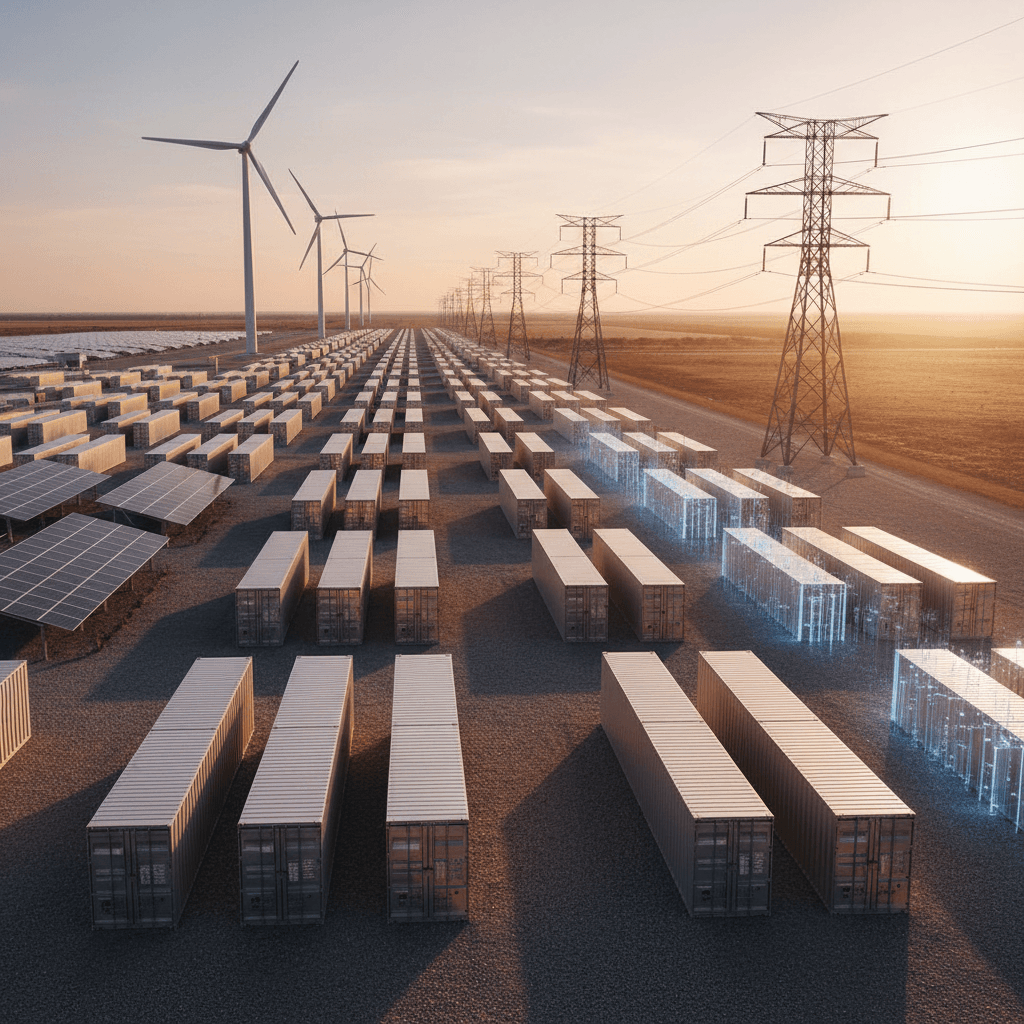

Most companies planning large-scale energy storage in 2026 still build models assuming lithium-ion is the only serious option on the table. Yet sodium–sulfur (NAS) batteries quietly racked up more than 5GWh of deployments and became the world’s second‑most‑used grid battery technology. Now NGK Insulators, the pioneer behind NAS, has decided to shut the product line down.

That decision, triggered after partner BASF exited the joint business, is more than a corporate reshuffle. It’s a warning light for anyone betting on alternative chemistries, and a reality check for how we finance long‑duration energy storage in the broader green technology ecosystem.

This matters because grid storage is the backbone of clean energy: without reliable, affordable storage, solar and wind stall out, and decarbonisation targets slip further away. The NAS story shows where the risks really sit – and how smart use of AI, better project design and sharper commercial discipline can keep green technology projects bankable.

NGK’s NAS batteries: a quiet giant steps off the stage

NGK Insulators’ decision is clear: the company has stopped manufacturing and selling sodium–sulfur NAS batteries and will no longer accept new orders. For a technology first deployed on the grid in 2003, that’s the end of a 20‑plus‑year run.

Here’s why that’s a big deal:

- NAS is the longest‑serving grid‑connected battery technology in commercial operation.

- More than 5GWh of NAS systems were deployed worldwide, mainly for utility and industrial storage.

- By deployed capacity, NAS was second only to lithium‑ion for grid‑scale batteries.

- For medium- to long‑duration energy storage (LDES), NAS was the most deployed electrochemical option after pumped hydro.

NGK’s NAS systems carved out a niche: 4–8 hour duration, high‑temperature operation, long calendar life, and the ability to sit in harsh environments where lithium-ion needed more protection or more complex fire‑safety engineering.

So why shut down now? The company hasn’t given a blow‑by‑blow public post‑mortem, but one factor stands out: BASF’s exit from the partnership removed both a commercial channel and a source of strategic support, forcing NGK to reassess the growth potential versus risk.

And here’s the uncomfortable truth: if a mature, field‑proven green technology with 5GWh deployed still can’t sustain a profitable growth path, the bar for newer “alternative” batteries is even higher.

What this tells us about the economics of long‑duration storage

The NAS story underlines a point a lot of investors quietly agree on: technical success doesn’t guarantee commercial viability for long‑duration energy storage.

Why long‑duration is hard to finance

LDES – systems that store energy for 4–24+ hours – is essential for high‑renewables grids. But it runs into brutal economic headwinds:

-

Value is complex to price

Long‑duration storage earns money from multiple value streams:- Arbitrage (charge when power is cheap, discharge when expensive)

- Capacity and resource adequacy payments

- Grid services (frequency support, voltage control)

- Congestion management and curtailment reduction

Most markets still don’t pay accurately for that stack, especially beyond 4 hours.

-

Capex is high and payback is slow

NAS and similar technologies often cost more per kWh upfront than mainstream lithium-ion. Whether they win depends on:- Longer life (more cycles)

- Higher usable energy (deeper discharge)

- Lower O&M If regulators and offtakers don’t lock in contracts that reflect those advantages, the financial model breaks.

-

Policy and market rules lag technology

Many power markets are built around thermal plants, not flexible storage. When rules don’t allow storage to fully participate – or treat it like a generator one minute and a consumer the next – projects struggle to capture their full value.

From what I’ve seen, most LDES failures aren’t really about chemistry. They’re about misaligned revenue models, fragmented incentives, and under‑modelled risk.

NGK’s NAS exit reinforces that: even a proven technology with two decades of field data can’t thrive if the market doesn’t pay fairly for what long‑duration storage delivers.

Lithium-ion vs alternatives: does NAS’s exit mean “winner takes all”?

The short answer: no – but the bar just moved higher for non‑lithium technologies.

Lithium‑ion dominates grid storage for good reasons:

- A massive supply chain built by the EV industry

- Falling costs per kWh and per kW

- Well‑understood performance and degradation patterns

- Bankability: lenders know how to price the risks

NAS, by contrast, offered:

- Higher operating temperature tolerance and no need for complex HVAC in some climates

- Long cycle life and good performance for 6–8 hour storage windows

- Better fit for some industrial and remote applications

But when BASF pulled back, NGK was left with a technology that was:

- Competing against ever‑cheaper lithium‑ion

- Operating in markets that still rarely pay a premium for longer duration

- Carrying the manufacturing and R&D burden essentially alone

For other alternative chemistries – sodium‑ion, flow batteries, zinc‑based systems, thermal and mechanical storage – the message is blunt:

A “green” or “safer” technology isn’t enough. You need a clear economic edge in a specific use case, and you need to prove it with hard data.

From a green technology strategy standpoint, that means:

- Don’t chase generic “grid storage” with a new chemistry. Own a narrow segment: e.g., 8–12 hour storage for weak grids, or ultra‑high cycling for industrial customers.

- Design standardised products and contracts that investors can understand and repeat.

- Use AI‑driven modelling to show, with evidence, where your technology wins over 10–20 years of operation.

Where AI fits: making green storage bankable, not just possible

Here’s the thing about AI in green technology: it’s rarely about inventing the physics. It’s about making complex systems financeable, dispatchable, and optimised in real time.

The NAS chapter closing doesn’t mean long‑duration storage has failed. It means the industry has to get sharper at proving value. AI is one of the most useful tools for that.

1. Smarter project design and siting

AI models can analyse years of:

- Historical load and price data

- Renewable generation shapes

- Network constraints

…and then recommend optimal storage duration, sizing and siting. Instead of “we think 8 hours might be useful,” you can say:

- “At this substation, a 6‑hour system increases renewable utilisation by 18% and reduces curtailment by 40%.”

- “Under current tariffs and ancillaries, IRR improves from 8% to 13% if we extend duration from 4 to 6 hours.”

That level of specificity is what turns an interesting technology into a bankable green infrastructure asset.

2. Predictive performance and degradation modelling

Degradation was one of the concerns often raised about high‑temperature systems like NAS, and it’s a critical point for any storage asset.

AI can:

- Predict capacity fade and efficiency loss for different operating strategies

- Optimise charge/discharge profiles to extend useful life

- Flag early‑stage anomalies that indicate safety or performance issues

For alternative chemistries trying to gain trust, being able to show transparent, AI‑backed performance projections over 10–20 years dramatically reduces perceived risk.

3. Monetising the full value stack in real time

Storage value is dynamic: prices change by the minute, policies update annually, and system needs evolve as more renewables connect.

AI‑driven dispatch systems can:

- Arbitrage day‑ahead and real‑time markets

- Prioritise the most lucrative combination of grid services each hour

- Adapt to new market products (for example, new flexibility or resource adequacy contracts)

For businesses deploying green technology, that’s crucial. The chemistry is the foundation, but software turns it into cash flow.

Practical guidance for developers, utilities and investors

If you’re planning or funding storage projects in 2026–2027, NGK’s NAS decision should change your filter, not your ambition.

For project developers

Focus on three disciplines:

- Chemistry–use‑case fit: Don’t default to lithium-ion or any alternative without mapping:

- Required duration and cycling

- Ambient conditions and safety constraints

- Local market products and tariffs

- Bankability from day one: Bring lenders and insurers into the conversation early. Their concerns around technology risk, warranty robustness and revenue certainty should shape your design.

- Data‑first pitching: Use AI‑supported modelling to show how your design performs across scenarios – price shocks, policy changes, extreme weather.

For utilities and grid operators

- Treat storage as infrastructure, not a gadget. Lock in long‑term contracts that properly value flexibility and long‑duration capability.

- Run system planning scenarios that compare:

- 4‑hour lithium‑ion vs 8‑hour alternatives

- Storage vs new transmission vs flexible demand

- Use AI tools to surface the cheapest path to reliability and decarbonisation, not just the cheapest capex.

For investors and corporate buyers

- Be wary of chemistries that only sell a story. Look for:

- Multi‑year field data

- Clear cost‑per‑delivered‑MWh logic, not just cost‑per‑installed‑kWh

- Transparent warranty and service structures

- Back teams that understand both electrochemistry and energy markets. One without the other is how you end up with technically sound, commercially stranded assets.

What NGK’s decision means for the future of green technology

NGK pulling the plug on NAS doesn’t mean long‑duration storage has failed. It means the market has passed judgment on one particular mix of chemistry, cost structure and commercial strategy.

For the broader green technology space, three things are clear:

- Green isn’t enough – technologies have to win on total lifetime value, not just sustainability credentials.

- AI is now a core part of storage competitiveness – in designing, operating and financing projects.

- Diversification still matters – relying purely on one battery chemistry is risky for grids aiming for deep decarbonisation.

If your organisation is planning storage, the better question isn’t “Is lithium‑ion the winner?” but “Where does each technology – backed by smart software – deliver the best economics and resilience?”

The companies that get this right won’t be the ones chasing every new chemistry. They’ll be the ones that treat grid storage as a system problem, use AI ruthlessly to quantify value, and pick technologies that fit specific, high‑value roles in a decarbonised energy mix.

That’s where green technology stops being a cost centre and starts behaving like a growth engine.