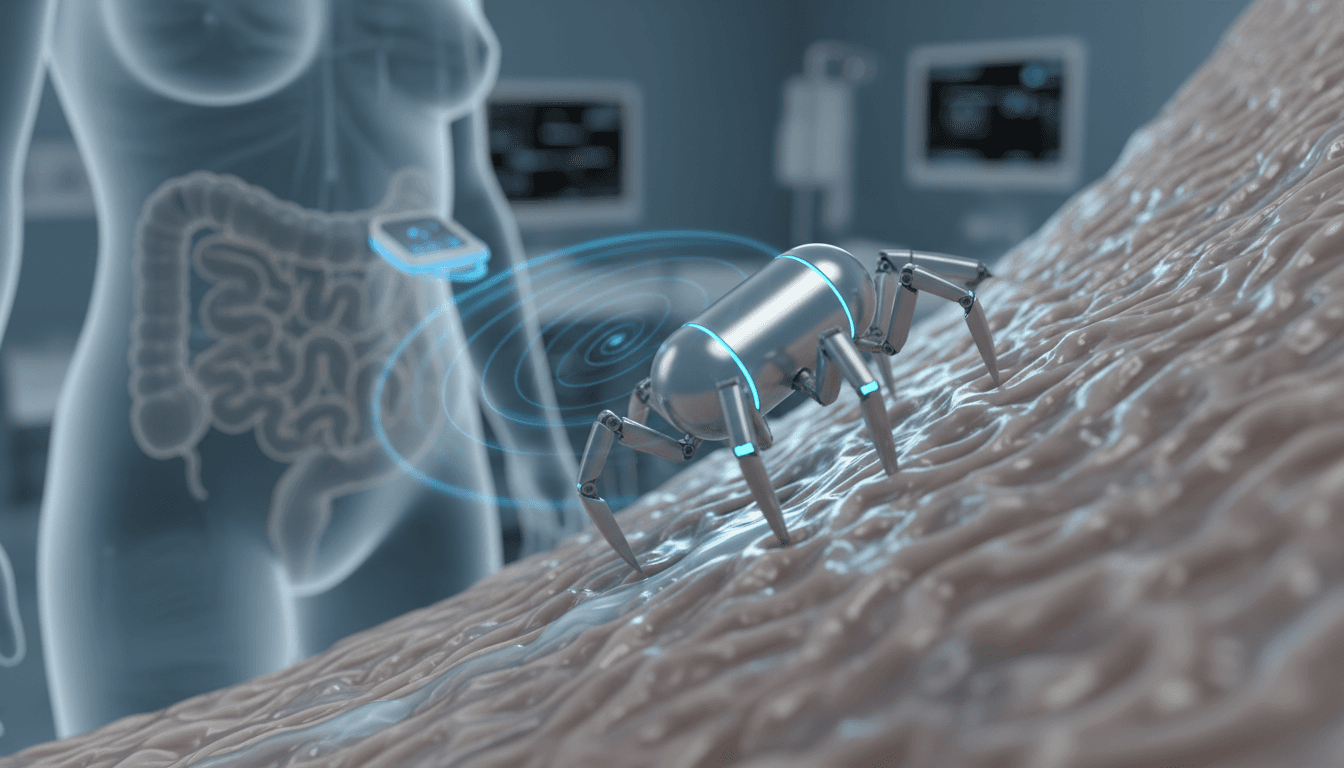

Pill-sized soft microbots may offer a safer, less invasive alternative to endoscopy—steered by magnets and guided by AI for precise gut diagnostics.

Pill-Sized Microbots for Safer Gut Cancer Screening

A standard colonoscopy can cost a patient a full day: prep, sedation, time off work, and the lingering “I really don’t want to do this again” feeling. That friction matters, because early detection is the biggest controllable factor in survival for many intestinal cancers—and yet plenty of people delay screening simply because the process is unpleasant.

Now zoom in to something the size of a large vitamin capsule: a soft, magnetically controlled micro-robot inspired by a spider that doesn’t crawl—it cartwheels. Researchers led by Qingsong Xu at the University of Macau have demonstrated a prototype that can move through the stomach, small intestine, and colon in animal tests, handling mucus, tight turns, and obstacles.

This isn’t sci-fi hype. It’s a concrete example of what our “Artificial Intelligence & Robotics: Transforming Industries Worldwide” series is really about: robots doing work that’s hard, risky, or dreaded by humans—with AI-guided precision and far less discomfort.

Why invasive gut diagnostics are a bottleneck

The problem isn’t that endoscopy and colonoscopy don’t work—they do. The problem is that too many people avoid them. Traditional endoscopes are flexible tubes inserted through the mouth or rectum to inspect internal tissue with a camera. The approach is effective, but it comes with trade-offs that scale poorly when you’re trying to screen large populations.

Here’s what makes current gut diagnostics a bottleneck for both patients and providers:

- Patient discomfort and anxiety: Sedation is common, and the anticipation alone keeps people away.

- Non-trivial risk profile: Improper manipulation can cause serious complications, including bowel perforation.

- Access limitations: Deep or complex regions can be difficult to reach depending on anatomy and pathology.

- Capacity constraints: Endoscopy suites require specialized staff and scheduling; it’s not an “on-demand” test.

If you’re a health system, this means late-stage diagnoses cost more and deliver worse outcomes. If you’re a patient, it means the best test is sometimes the one you’ll actually agree to take.

The microbot approach: swallowable, soft, and steerable

The central idea is simple: replace the uncomfortable tube with a swallowable robot you can steer from outside the body. Xu’s team built a soft robot roughly the size of a capsule, made from a rubber-like magnetic material. It’s designed to travel through the gastrointestinal tract and perform inspection tasks—without the same level of discomfort.

Unlike passive capsule endoscopes (which largely drift with natural peristalsis), this category of device aims for active navigation using an external magnetic field.

How the “spider” robot moves (and why cartwheeling matters)

Most people assume a robot inside the body should “crawl” like a worm. The Macau team took a different route.

Their inspiration: the golden wheel spider, a small arachnid (about 2 cm wide) known for escaping danger by tucking in its legs and rolling down dunes. The robot mimics that rolling behavior—except it doesn’t rely on gravity. It rolls using magnetic forces interacting with tiny magnets embedded in its legs.

That locomotion choice isn’t cosmetic. In the gut, the robot has to deal with:

- Mucus-slick surfaces that defeat traction-dependent designs

- Folded tissue and variable geometry

- Vertical or inclined sections where sliding and stalling are real problems

- Obstacles and sharp turns that can jam rigid or shape-limited devices

Rolling/cartwheeling can be more stable and energy-efficient than other modes when the surface conditions are inconsistent—exactly what you get in a living digestive tract.

The control setup: magnetic fields plus robotic positioning

To steer the robot precisely, researchers used a robotic arm holding a powerful rotating magnet positioned next to the patient (or test subject). The external magnet generates a controllable field; the robot responds by rolling and reorienting.

This is where the broader campaign theme shows up: robots don’t become medical products just because they move—control is everything. And control increasingly depends on software.

Even if the prototype is magnet-driven, the long-term path to clinical adoption almost certainly includes:

- AI-assisted planning: choosing routes and behaviors based on anatomy and imaging

- Closed-loop control: adjusting magnetic actuation in real time using camera feedback

- Safety constraints: algorithmic “guardrails” to prevent excessive force on tissue

In practice, the “microbot” is a system: device + magnetic actuation hardware + sensing + control software.

What makes soft magnetic robots promising for real clinics

Soft robotics is a better fit for the human body than rigid mechanisms. Hard devices scrape, pinch, or bruise tissue when something goes wrong. A soft body can deform and yield.

Xu’s group reports the robot handled “complex environments” in animal tests—mucus, sharp turns, and obstacles as high as 8 cm. That’s the kind of detail that matters, because GI navigation fails in very specific ways: stalling, slipping, losing orientation, or getting stuck.

Beyond imaging: targeted drug delivery and micro-interventions

A strong stance: diagnostics alone won’t be the endpoint. If micro-robots make it into clinical workflows, the bigger payoff is combining diagnosis with early intervention.

The RSS summary highlights demonstrations of targeted drug delivery. That opens the door to practical use cases like:

- delivering localized therapy to an ulcer bed

- applying medication near an inflamed region in Crohn’s disease

- positioning near suspicious lesions for higher-quality imaging

A related example from North Carolina State University shows a caterpillar-like soft robot that crawls via magnetically induced contractions in an origami-style structure and has been tested delivering mock treatment to a mock stomach ulcer.

The pattern is clear: teams are trying multiple locomotion strategies (rolling, crawling, swimming, jumping). The winners will be the designs that handle the messy reality of anatomy, not the clean geometry of lab tubes.

How AI fits in (and why it’s not optional)

People hear “magnetically controlled robot” and assume it’s basically a joystick problem. In early prototypes, maybe. In clinical scale-up, no.

AI becomes essential when you need consistent performance across thousands of bodies with different anatomy, motility patterns, and pathology. The AI contributions are likely to cluster in four areas:

- Computer vision for mucosal inspection: detecting polyps, bleeding, inflammation patterns, and suspicious textures.

- Autonomy assist: “suggested maneuvers” or partial automation to reduce operator workload.

- Quality assurance: scoring whether a region was adequately inspected (similar to how AI already helps in colonoscopy quality metrics).

- Personalization: adapting navigation strategies to patient-specific anatomy and motility.

Put bluntly: the robot is the hand; AI becomes the situational awareness.

What needs to happen before pill-sized microbots replace endoscopy

No magnetically controlled soft micro-robots are mainstream clinical tools yet, and that gap is worth respecting. The Macau team is aiming for more live-animal experiments and then human clinical trials, with an optimistic timeline of around five years for early clinical impact.

To get from prototype to routine care, several hurdles must be cleared.

Safety, reliability, and “what if it fails?” scenarios

Regulators and hospitals will ask the same questions patients do:

- What happens if the robot stops moving?

- Can it be retrieved safely?

- How do you prevent overheating or excessive force from magnetic actuation?

- What’s the risk of retention in strictures or narrowed segments?

Soft materials help, but clinical safety is about systems engineering: fail-safes, retrieval plans, and robust testing across edge cases.

Imaging quality and clinical usefulness

A capsule that’s comfortable but delivers low-quality imaging won’t replace endoscopy. To compete, microbots need:

- stable orientation for clear visuals

- controllable dwell time (stay and inspect)

- adequate lighting and resolution

- reliable localization (knowing where you are)

That last point—localization—is a quiet make-or-break feature. AI-based mapping and magnetic field modeling will likely be part of the solution.

Workflow fit: the technology must reduce friction, not add it

Hospitals won’t adopt a system that requires a physics PhD in the procedure room.

The winning product will be the one that:

- fits into existing gastroenterology workflows

- reduces sedation needs and recovery time

- produces standardized reports clinicians trust

- shortens procedure time, not lengthens it

This is also where leads are born: health systems are actively looking for technologies that increase screening throughput without burning out staff.

Practical takeaways for healthcare leaders and innovators

If you’re evaluating AI-powered robotics in healthcare, microbots are a strong test case because they combine clear patient value with measurable operational upside. Here are the questions I’d use to separate serious platforms from flashy demos.

For providers and health system decision-makers

- Ask what replaces sedation: Is the target use case screening without sedation, or just “less uncomfortable endoscopy”? Those are different ROI stories.

- Demand quality metrics: What defines “complete inspection” in this system, and how is it audited?

- Plan for exceptions: Retention, retrieval, strictures—get the protocol in writing early.

- Assess training burden: How many cases to competency? What does day-one usability look like?

For medtech and robotics teams

- Design for the worst anatomy, not the average: strictures, motility issues, adhesions, mucus variability.

- Build AI for operator confidence: highlight uncertainty, flag blind spots, and log everything.

- Treat localization as a core feature: “pretty video” isn’t enough without location context.

- Prove manufacturability: soft robots live or die by repeatable material properties and consistent magnet placement.

Where this fits in the bigger robotics story

Robotics is steadily moving from factories into environments that are moist, unpredictable, and high-stakes—like the human body. That shift is why this microbot matters beyond gastroenterology.

Soft magnetic micro-robots show a broader industrial pattern: when sensors get cheaper, controls get smarter, and form factors get smaller, whole categories of “accepted pain” in workflows start to look optional.

If you’re tracking how AI and robotics are transforming industries worldwide, watch this space closely. A pill-sized robot that can inspect, map, and eventually treat tissue isn’t just a new gadget—it’s a new delivery model for care.

The next real question isn’t “can the robot roll through the gut?” It’s: when the robot finds something early, can the system act fast enough to change the outcome?

If you’re exploring AI-powered robotics for clinical operations or medtech partnerships, focus on solutions that reduce patient friction and increase diagnostic certainty—those are the ones that earn adoption.