Explainable AI helps autonomous vehicles reveal why they act—improving safety, accountability, and trust. See practical XAI patterns that prevent failures.

Explainable AI: The Missing Safety Layer in Self-Driving

A self-driving car misread a 35 mph speed limit sign as 85 mph after a small sticker altered the shape of the “3.” The car accelerated.

That story sticks because it’s not really about a sticker. It’s about a broader, uncomfortable truth: autonomous vehicle (AV) perception and decision-making can fail in ways that look “reasonable” to the machine and completely unacceptable to humans. When that gap isn’t visible, trust collapses—fast.

In our “Artificial Intelligence & Robotics: Transforming Industries Worldwide” series, we’ve looked at automation that boosts speed and efficiency. Autonomous vehicles are different. On public roads, efficiency is secondary. Safety, accountability, and human confidence are the product. Explainable AI is becoming the practical way to deliver all three—by making vehicles answer the right questions at the right time.

The core problem: AVs are competent—and still opaque

Autonomous driving stacks are often black boxes to everyone except the engineering team. Passengers don’t know what the car “thinks” it sees, what it’s prioritizing, or why it’s taking action.

That matters because modern AV systems aren’t a single algorithm. They’re a pipeline:

- Perception (detect lanes, vehicles, pedestrians, signs)

- Prediction (estimate what others will do next)

- Planning (choose a safe, legal trajectory)

- Control (steer, brake, accelerate)

When something goes wrong, the question isn’t just “Why did it crash?” It’s:

- Did perception misread the world?

- Did prediction over/underestimate risk?

- Did planning choose an unsafe tradeoff?

- Did control execute poorly?

Explainable AI (XAI) brings visibility to those steps by letting the system provide interpretable reasons for actions—either in real time or through after-the-fact analysis.

“Autonomous driving architecture is generally a black box.” — Shahin Atakishiyev (University of Alberta)

Why transparency is a safety feature, not a nice-to-have

Most companies treat explainability as PR—something to reassure regulators and the public. That’s a mistake. The primary value is operational: XAI helps teams locate failure points faster and design better safeguards.

Think of it like aviation. Pilots don’t trust autopilot because it’s perfect. They trust it because they have:

- cockpit instrumentation,

- explicit modes,

- warnings,

- checklists,

- post-incident investigation tools.

Autonomous vehicles need their equivalent set of “instruments.” Explainable AI is a key piece.

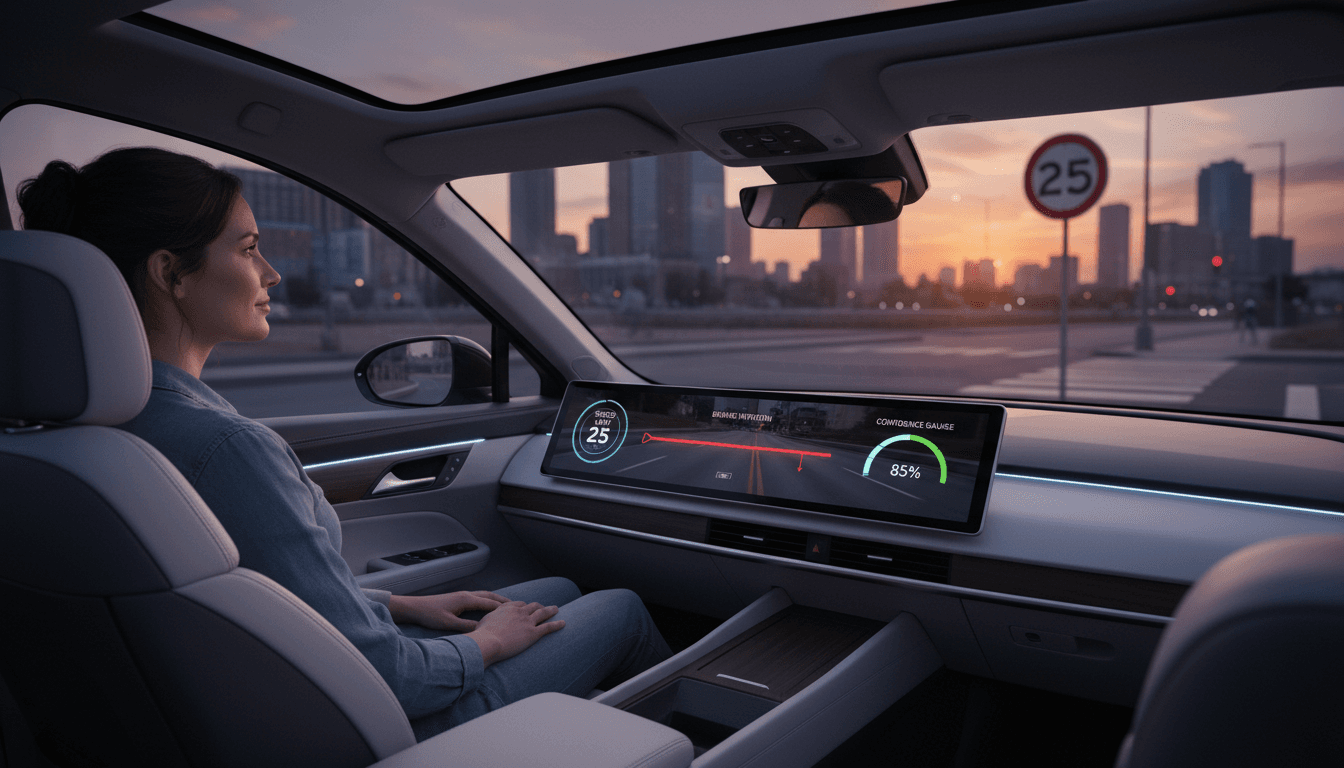

Real-time explanations: giving passengers the right “intervention moment”

The best time to prevent an incident is before it happens. Atakishiyev and colleagues describe how real-time rationales could help passengers recognize faulty decisions in the moment.

Revisit the altered speed sign scenario: if the vehicle displayed something like:

- “Speed limit detected: 85 mph → accelerating”

…a human passenger could override, slow down, or disengage automation.

The design challenge: explanations that don’t overload humans

Real-time explanations can backfire if they become noise. A dashboard filled with model internals doesn’t help the average person at 70 mph.

A practical approach is tiered explainability, similar to medical devices:

- Tier 1 (consumer-facing): short, plain-language intent statements

- “Slowing: pedestrian near crosswalk”

- “Changing lanes: vehicle stopped ahead”

- Tier 2 (power user/fleet operator): confidence + sensor cues

- “Sign read: 85 mph (confidence 0.62), camera-only”

- Tier 3 (engineering/debug): feature attributions, raw detections, time-series traces

And delivery mode matters. As the researchers note, explanations can be provided via:

- audio cues,

- visual indicators,

- text,

- haptic alerts (vibration).

My stance: for consumer vehicles, the default should be minimal, actionable, and interruptive only when risk is rising. In other words, don’t narrate the whole drive—surface explanations when the car’s certainty drops or when it’s about to do something unusual.

“People also ask”: should passengers really be expected to intervene?

Passengers shouldn’t be the primary safety system. But in real deployments—especially Level 2/Level 3 mixed-control environments—humans are already part of the safety loop.

Explainability helps by answering a simple, crucial question:

“Is the car operating within its confidence envelope right now?”

Even a small improvement in the timing of handover requests can reduce risk. The real win is not shifting blame to the human; it’s making the automation’s limits visible.

Post-drive explainability: debugging the decision pipeline

After-the-fact explanations are where engineering teams get compounding returns. Every misclassification, near-miss, or harsh braking event can become a structured learning artifact.

Atakishiyev’s team used simulations where a deep learning driving model made decisions, and the researchers asked it questions—including “trick questions” designed to expose when the model couldn’t coherently justify its actions.

That approach is valuable because it tests a subtle failure mode:

- The model can output the “right” action sometimes,

- but can’t reliably explain the cause,

- which signals brittle reasoning and poor generalization.

The questions that actually find safety bugs

If you’re building or evaluating autonomous driving AI, generic “why did you do that?” prompts aren’t enough. Better questions isolate the pipeline stage:

- Perception checks:

- “Which pixels/regions influenced the speed-limit classification most?”

- “Which sensor dominated this decision—camera, radar, lidar?”

- Counterfactual checks:

- “If the sign were partially occluded, would you still accelerate?”

- “If the pedestrian were 1 meter closer, would you brake earlier?”

- Timing and latency checks:

- “How did time-to-collision estimates change over the last 2 seconds?”

- “Was the plan computed under a degraded compute budget?”

- Policy/constraint checks:

- “Which rule constrained the planner most—lane boundary, speed limit, following distance?”

A good explanation system doesn’t just narrate decisions. It helps you locate the broken component.

SHAP and feature attribution: useful, but only if you treat it carefully

The RSS summary highlights SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP), a method that scores how influential different features were in a model’s output.

Answer first: SHAP is helpful for identifying what the model relied on, but it’s not a substitute for safety validation.

Here’s how it creates value in AV development:

- It can reveal when a model relies heavily on spurious cues (e.g., background patterns near signs).

- It can show which inputs are consistently ignored, suggesting wasted complexity.

- It supports model audits after incidents by providing a ranked list of influential signals.

Where teams get SHAP wrong in autonomous vehicles

Feature attribution is often treated like truth. It isn’t.

Common pitfalls:

- Attribution ≠ causation. A feature can correlate with an output without being the true reason the system should trust it.

- Attribution can be unstable across small perturbations—ironically the same problem AVs face in the real world.

- Global vs local confusion. A feature that matters on average may be irrelevant in the exact moment a near-miss occurred.

A better practice is to pair SHAP-style methods with scenario-based testing:

- run the same scene with controlled changes (lighting, occlusion, sign damage),

- compare both decisions and attributions,

- flag conditions where reliance shifts abruptly.

That’s how explainable AI becomes an engineering tool, not a visualization demo.

Explainability and liability: what the car “knew” matters

When an autonomous vehicle hits a pedestrian, the technical questions quickly become legal and operational ones.

Explainable AI can help answer key post-incident questions, such as:

- Rule compliance: Was the vehicle following road rules (speed, right-of-way, signals)?

- Situational awareness: Did the system correctly detect a person vs. an object?

- Appropriate response: Did it brake, stop, and remain stopped?

- Emergency behavior: Did it trigger emergency protocols (alerts, reporting, hazard lights)?

Answer first: in regulated environments, “the model decided X” isn’t enough. You need a traceable account of what inputs mattered and which constraints were applied.

From an industry perspective, this is where AI and robotics are maturing: not just doing work, but producing audit-ready evidence of safe operation. The same pattern is showing up in warehouses, factories, and healthcare robotics—systems need to explain their actions when safety and liability are on the line.

A practical framework: “explain to three audiences”

If you’re deploying autonomous systems in any industry, build explanations for three groups:

- End users (passengers, operators)

- Investigators (safety teams, regulators, insurers)

- Builders (ML engineers, robotics teams)

One explanation UI can’t serve all three well. Separate them, and you’ll ship something people can actually use.

What safer autonomous vehicles look like in 2026: a short checklist

Explainable AI is becoming “integral,” as Atakishiyev argues, but the bar for safety should be concrete.

Here’s what I look for when evaluating an AV program—or any AI-driven robotics system operating around humans:

- Real-time intent + uncertainty: the system signals not only what it’s doing, but how sure it is.

- Scenario-triggered explanations: more detail appears when risk rises (odd signage, construction zones, low visibility).

- Post-event replay with attribution: teams can reconstruct perception → prediction → plan, with timestamps.

- Counterfactual testing baked into QA: “What if the sign is dirty?” isn’t an afterthought.

- Human handoff protocols that are measurable: handoff timing, clarity, and success rates are tracked like safety KPIs.

These are not academic extras. They’re how autonomy becomes dependable infrastructure.

Where this fits in AI & robotics transforming industries

Autonomous vehicles are a headline application of AI and robotics, but the lesson travels well: the more autonomy you deploy, the more you need explainability to keep humans in control.

Factories want robots that can justify why a safety stop triggered. Hospitals need clinical AI that can explain why it flagged a patient as high risk. Logistics networks need route-optimization systems that can justify why they changed a plan mid-shift.

Self-driving tech just happens to be the most visible—and the most unforgiving—place to learn this lesson.

If you’re exploring autonomous systems for your business, the next step isn’t “add more sensors” or “train a bigger model.” It’s building an autonomy stack that can answer hard questions under pressure.

If your autonomous system can’t explain itself, you don’t have autonomy—you have a liability.

Where do you think explainability will matter most over the next two years: consumer AVs, robotaxis, industrial robotics, or healthcare automation?